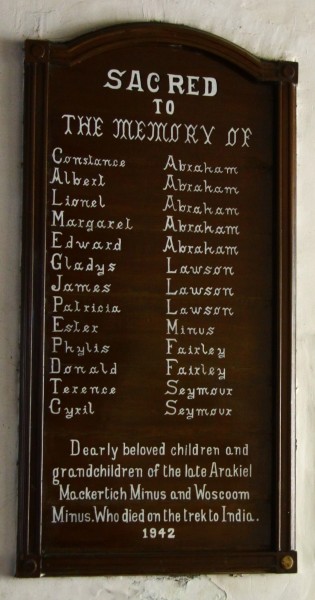

My family came to Canada when I was very young, so I did not have the usual extended family of aunts, uncles and cousins, although I was lucky to have my maternal grandmother living with us. I think because I was an only child, unused to extended families, I never felt much interest when Dad mentioned his aunts had done a trek. I got the impression they had trekked from Armenia to Burma before he was born; for whatever reason, he did not go into any detail about the trek. He must have known all about it, because after his only trip back to Burma in 1997, he told me there was a plaque in the Armenian church about them ‘because of the War,’ as he put it. Again, he didn’t explain and I just assumed it was the usual burial plaques one finds in Christian churches all over the world. That assumption could not have been more wrong.

At the end of 2012, I decided to visit Burma very suddenly, without too much planning. A friend put me in touch with a Burmese travel agent, who suggested itineraries and booked flights and hotels. She was aghast that I wanted to spend so much time in Rangoon, three days either side of our tour. What would I be doing? Well, armed with old maps of the city, Arthur’s hand drawn map of Coffee Grove and the address of the Armenian Church, I was going on the ‘Minus Trail,’ as we called it. Due to researching the family tree, I had stumbled on a story that explained the aunts’ mysterious trek.

For those of you as unfamiliar as I was with WWII in Burma, I give a short background below:

On the 23rd of December, 1941 and again on Christmas Day, the Japanese bombed Rangoon. Although it was known they were in the country, they had confined their previous attacks far to the southeast. It was a complete surprise. and set in motion a tragedy that is often referred to as ‘the Forgotten War.’ There are many learned books about the fall of Rangoon, but the one I found most readable and accurate is ‘Last and First in Burma (1941-1948)’ by Maurice Collis. I will be quoting him extensively over the next few paragraphs.

‘The streets were crowded with people, the Burmese, Indians and Chinese who made up the population of 400,000. They did not at once realize their danger; the planes seemed so high and far away. An official account states: ‘Along Strand Road hundreds of Indian coolies were interested spectators of the dog fights overhead; on these unfortunates stick after stick of anti-personnel bombs rained down.’ In a moment the pavements were strewn with the dead and dying. There followed a terrible panic. The civil defence, rescue and medical services broke down because nearly all their staff fled the city…. Altogether 2,000 people were killed, 750 died later and 1,700 were wounded.’

Forty fires were started and only by a supreme effort was the city full of teak houses prevented from burning to the ground. The second bombing on Christmas day wiped out nearly all the military aircraft at Mingaladon airport. After this there was a stream of refugees heading north to India. Over the next two months the Governor, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith tried to get troops from Churchill, the Australians and our Chinese ally, Chiang Kai-Shek, but did not succeed. Things deteriorated; there was uncontrolled looting, the shops, bazaars and banks were shut and every ship that tried to take away refugees was in danger of being swamped by refugees who clambered over barbed wire, stepping on women and children. Some lucky people flew out when the planes were still operating, but as time went on it became impossible. Eventually the order came on March 8th to completely evacuate Rangoon, while making sure anything the enemy could use was destroyed. So, charges were laid in the docks and the great oil refineries across the river in Syriam, then set off by the last-ditchers. The inmates in Insein prison were released and so were the inhabitants of the lunatic asylum, because there was no food left and no one left to look after them. The man who gave this order was so disturbed at the chaos that resulted that he committed suicide the next day. At the leper colony the nuns said they would stay and God would provide. Even the Zoo was not spared; dangerous animals like the tigers, crocodiles and snakes were shot and the rest set free.

My great aunts had no government connections. They were solid middle class families, whose husbands ran their own small businesses or worked for the great British corporations. The aunts were used to having servants and spent their time visiting, shopping, doing good works for the Church and raising their children. At some point between Christmas 1941 and the end of February 1942 they left their comfortable houses, their cooks, chauffeurs, punkah-wallahs and ayahs and began their trek.

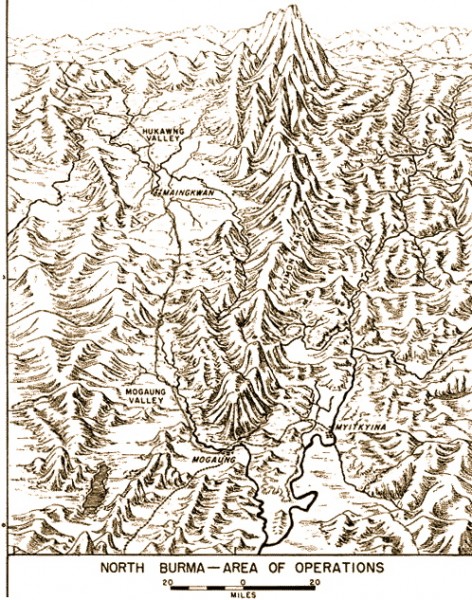

My belief, after reading about many others who did the same, was that they either left Rangoon late, or stayed in one of the towns in the north too long, because the route they chose over the mountains into India was through the Hukawng Valley. This route was infamous.

“In its [Myitkyina, a city in northern Burma] latitude was the Hukawng Valley, an exit to India in name only, as it involved a march of a hundred and fifty miles (as the crow flies) to the Indian border over roadless mountains, unmapped and largely unexplored, uninhabited, foodless and rank with malaria, a route which would for a well equipped exploring expedition (in the fine season) have been quite an adventure, but which for straggling refugees in the monsoon (due 15 May) was going to be like entering the Valley of the Shadow of Death.”

The refugees not only endured endless steep climbs, but endless deep mud and leeches. A leech would drop from a branch, climb up a stalk of grass or be brushed from a leaf onto a passing body. It would make a hole in the skin, latch on and suck blood until it was engorged like a small cigarette. The holes became septic and turned into jungle sores. There was no way to dry out shoes, clothing or packs, no level dry camping spot to sleep in overnight.

“What it is like to be drenched in the monsoon when marching through a tract of jungle-covered mountains two hundred and fifty miles wide is difficult for us here to imagine. It means mud to the knees on the level, slippery ascents hardly possible to climb, malaria in its worst forms, dysentery, assault by leeches (both the ordinary and the brown tiger breed) that drop from the trees, start from the grass, reach out from the bushes, and by sandflies, a worse torture than mosquitoes. It means, too, streams that become cataracts and cannot be crossed; nights in soaking clothes in a dripping lean-to; impossibility often of lighting a fire; and a cruel depression of the spirits.”

A refugee who trekked out with a party of seventeen men and women noted:

“There were plenty of dead bodies on the side of the road, but worse than these were the people tottering along or sitting by the wayside suffering from pneumonia and exhaustion.”

Another diary from a refugee states:

“And then we saw elderly men and women standing weeping at difficult corners which they had not strength to go round. Then as we climbed further we came across dead animals and dying people… At one corner I tried four times to get round, finally clawing up on hands and knees.”

The last quote on this terrible tragedy is from Professor Pearn:

“Few of the refugees had any experience of jungle life, and these wild and inhospitable hills must have filled them with terror….The longer the journey lasted, the more the strain began to tell….If a member of a party fell by the wayside he was left; husbands deserted wives who could not maintain the pace, sons deserted parents, even mothers deserted children.”

There were seven great-aunts, all sisters to my grandfather, Mackertich Minus. Three died on the trek. Here is what I know of some of them and their children from the 1942 Trek casualty lists published on the Anglo-Burmese Library website:

Mr. and Mrs. Lawson (nee Gladys Minus, 1900-1942) and a daughter died on the hill route from Sumprabum to Shinbwiyang. Reported by Miss G. Marshner at Margherita. The other daughter is reported by Miss G. Marshner to have been murdered by Kachins at Daikpone. Mr. Lawson was of the Motor House, Rangoon.

Miss Ester Minus (b.? d. 1942) died on the way to Shinbwiyang on the hill route from Sumprabum. Reported by Miss G. Marshner. Margherita report, dated 6th Nov. 1942.

Mr. Seymour, 17 years (son of Bertha Seymour, nee Minus) murdered by the Kachins at Daikpone. Information given by by Miss G. Marshner at Margherita.

Here is what I know about the others who aren’t on any lists:

Constance Abraham (1895-1942) was married to Victor “Vahoo” Abraham. He worked for the Irrawaddy Flotilla company, whose boats were a lifeline in Burma, where there were few major roads. Early in 1942 he was asked to stay on in Rangoon as long as possible and he agreed to do so as long as his wife and children could have a free passage to safety on one of the company’s boats. At the last minute the company did not honour their pledge, so Connie and her children trekked out and all of them died. Vahoo met my uncle after the war. He had had a nervous breakdown and was never the same again.

Phyllis Fairley was the daughter of Bertha Seymour, nee Minus, one of grandfather’s sisters. Phyllis died, Bertha survived and was the first relative to welcome my uncle Arthur back after the war, in 1946.

As I said earlier, I knew this before I went to Rangoon. I had told my daughter, who accompanied me and of course, we felt sad about these women we had never met, but whose genes we shared. I looked forward to seeing the plaque.

The day after we arrived we walked to the Armenian Apostolic Church of St. John the Baptist. The temperature at 9:00 in the morning was already in the 70’s. We arrived twenty minutes later and entered the side gate to be met by the Father in charge. The plaque was in a breezeway, sort of a large porte-cochere. It was made of a dark wood with the details painted in white. I started to read it and then stopped. I couldn’t go on.

I cried, no – I sobbed. I cried for the great-aunts and cousins I never knew. I cried for the horrible sacrifices and decisions they must have made on the trek. I cried because there shouldn’t be any wars, but if there must, they should be fought by soldiers, not civilians. I cried because I had been disinterested in the family history until it was too late to ask the people who knew.

I had to walk away and look into the unkempt garden before I regained control. Everyone was embarrassed, but too polite to say anything. At that moment I knew I would do everything I could to preserve their history, tell their story and make sure it was never forgotten.

Hello Chinthe, I was so interested to find your website. My family also lived in Burma from at least the mid-19th century. They lived in Kokine and trekked out by different routes in 1942. After spending the war years in Mussouri, they ended up in south London. I have various diaries and notes and first started writing it all up as a novel about 30 years ago. I’m now going back to it and revising it and am beginning to feel inspired to travel to Burma to try to track family that are still there and would love to do the steamer trip up the Chindwin, where my aunts started their route out. There are definitely still people there with the family name.

Hi Jean,

You are so lucky to have family diaries! How I wish I did.

I encourage you to go, you won’t regret it. I have just been talking to a friend of mine who lives here in Canada, but is a guide with many tour companies in SE Asia. She has just lectured on two cruises in Burma: one on the Chindwin and one on the Irrawaddy. The trips sounded wonderful. I will be going on my second visit in less than two weeks time, to explore the family connections more deeply. I hope to come back with some questions answered, or at least more stories and great pictures.

Hi Chinthe

Robin McGuire, the deputy commissioner of Myitkyina to whom you refer in your article, was my grandfather. I was not aware he kept a diary of the trek and, although I knew some things about it, the information you have provided is new. What else do you know and where can we see the diary? Incidentally he navigated the Hukawng Valley partly with the aid of a map imprinted on a silk scarf which I now have. In January 1943 he was awarded an OBE in recognition of his efforts to help the thousands of refugees who fled via this route.

Hi Jean,

I was researching the Armenians in Rangoon and came across your website. I enjoyed reading the article “The Trek of the Great Aunts”. The terrain in Burma can be terribly inhospitable, especially the jungles and mountains in the Hukawng Valley in the north west that you refer to. My parents were not able to escape the clutches of the Japanese soldiers and ended up being interned first in Myitkyina and a couple of years later in Ft. Dufferin in Mandalay.

I’m currently writing an article for the Anglo-Burmese Library (based in London, UK) on the OSS Detachment 101 activities in Burma during WW2. One of the individuals I’m writing about is Aram (Bunny) Aganoor, a 2nd Lieutenant in Det. 101.

Bunny was from a Rangoon Armenian family and attended the Diocesan School in Rangoon. He was with my uncle (Major Patrick “Red” Maddox) and part of Team A that was parachuted into Burma behind Japanese lines to blow up the bridges. Unfortunately, he was caught by the Japanese and renegade Burmese and killed in early 1943. Bunny was the first fatality of Det. 101. He laid down his life by fighting a rear guard action so that his team mate, Pat Quinn, could escape.

Bunny was never credited by by the US Armed Forces for his valour. I wanted to make sure that he at least is given full recognition in the project on OSS Det. 101 that I’m working on. His exploits, however short, are of great credit to the Armenian community in Rangoon. I’ll be glad to send you the article on Bunny when it’s finished. Let me know if you are interested.

Sincerely,

John Mealin

Dear Chinthe and John,

My daughter Lucille sent me a link to the article, which I found very interesting. I find it hard to keep up with research but I know I should preserve my uncle’s memory. I know my daughter Lucille is especially interested and for her sake I should look into it all. I have wondered if you have finished the report you were doing about my late uncle Bunny who was killed in action.

Lucille is living in Berlin Germany so we don’t see her very often but she is a very thoughtful person and sent me the link yesterday and another about my mother Stella evacuation of Burma only I know she travelled by ship not the very dangerous treck on foot that sadly causes the huge loss of life.

Moira Bradey, Darlington UK

Greetings Chinthe and my sincere thanks for sharing. My pregnant Mum was a last moment addition to the last refugee plane to make it out of Myitkina before the field was strafed. Dad got out by boat after helping destroy things in Rangoon & volunteered to go back & help destroy oilfields, then trekked out through the valley. I spent years at the feet of Dad, my Uncles & their friends who survived. Listening to stories of Burma & The Trek, reading their maps/scraps of diary etc. Am in the early days of writing a family biography & names include Reisch/Hawken/Tingley/Smart/Quinconroy/Chettle/Neve/Shaw etc.

All strength to you and as Burma is high on our visit list, should your Myanmar travel agent contact not mind, would appreciate any contact detail you may care to offer.

Sincerely, Roger Tingley

Dear Roger,

You are so fortunate to be able to listen to those stories first-hand. I never met any of my great-aunts, so have very little information about them. As for travel agents, I didn’t use one last time as I was staying in Rangoon the entire time. If I go again I think I would try to research local Burmese agents in each part of the country I would like to visit. So many more of them have websites now, and although the Internet is slow, they eventually answer.

Roger – Patsy Evans from Australia here – did you ever get to writing your story? I am also in midst of writing my father and mothers story – Rangoon, trekking out through the jungle, returning to Rangoon then leaving. Would love to hear from you

Your photograph collection is incredible, for which many thanks. I’d like to draw your attention to my book, Exodus Burma which was first published by The History Press in 2011 and in paperback in 2017. I was lucky enough to read many accounts by survivors of that trek and to meet a few of the people who made that journey. The contrast between the wonderful almost charmed lives led in pre-war Rangoon and the escape through the jungle struck me so forcibly. My 95 year old Dad served in Burma during World War II which is what led to my interest. I gave a talk last year at a history group and a woman of Armenian heritage approached me afterwards, sadly I didn’t get her name as she rushed off afterwards, but she lost family members on the trek and like so many others, was not aware of their fate.

Felicity,

Your book was the first I read about the Trek and it opened my eyes as to what my great-aunts must have endured. As you say, a life of ease and plenty, not only cut short, but then an horrific journey like something out of Dante’s Inferno. I am sure you have met people who have never hesrd of it, but know all about Dunkirk and other setbacks during WWII. I think the Trek needs to be featured in a major film, or perhaps a documentary, with modern “survivalists” undergoing the same journey. Thank you so much for capturing the memories of survivors for posterity.

Sharman