The name A.C. Martin means very little to people now, except for the handful of remaining descendants of the Armenian community living in Yangon today. If you have been to Yangon, Myanmar, you have walked past some of A. C Martin’s buildings including the General Post Office, which used to house the offices of Bullock Brothers & Co., a pre-eminent rice trading company. If you missed this, you almost certainly have walked on the roads he built.

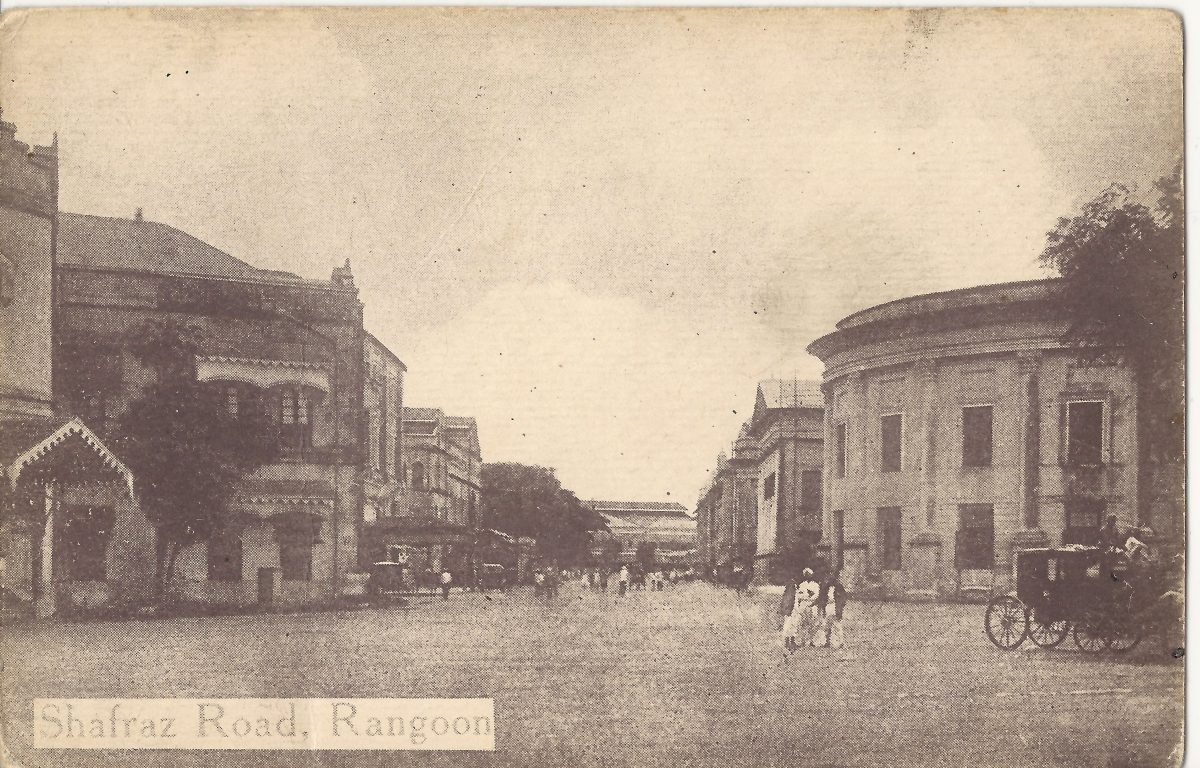

Shafraz Road, named after another Armenian

If you were lucky enough to have a knowledgeable guide, as I did a few years ago, you might have climbed the betel stained stairs above some shops, and seen the plaque bearing his name.

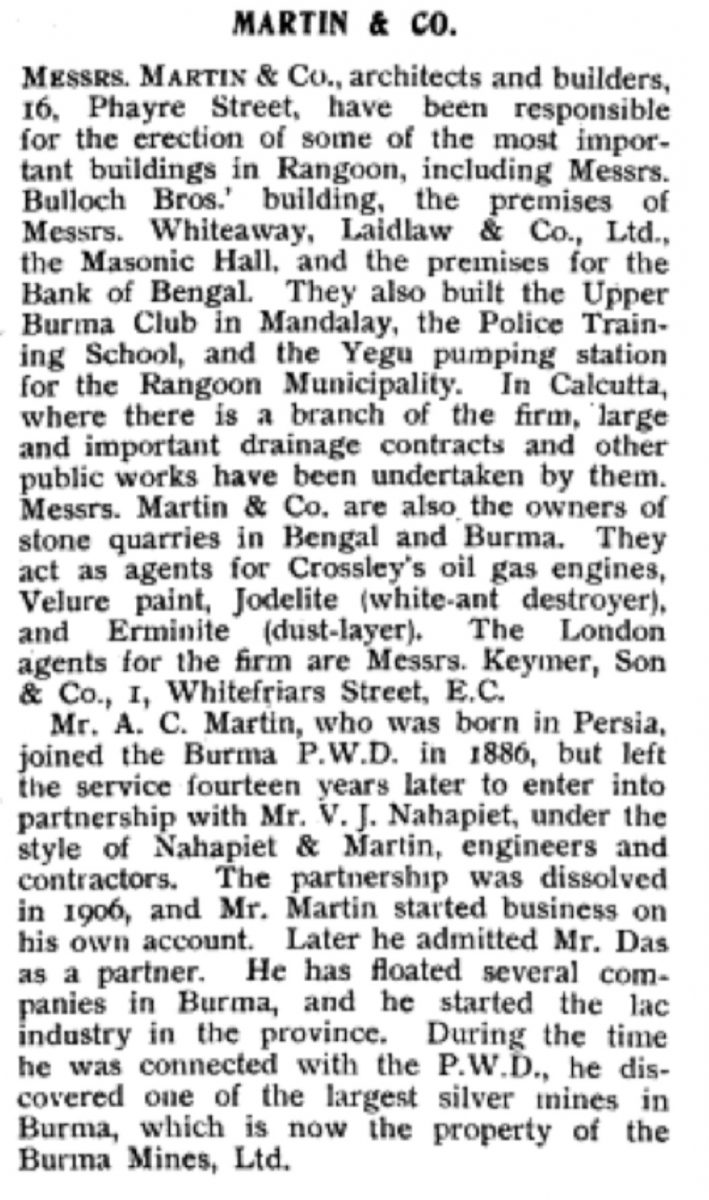

However obscure his name is today, in the late 19th and early 20th century he was well known in the Armenian community and the Rangoon Public Works Department as a superb engineer and builder. Below is an excerpt from a book on Burma, published in 1910, “Twentieth Century Impressions of Burma”. Read his biography and note the date. Five years later, Mr. Martin was tricked out of a fortune by the petty machinations of a District Commissioner in Tavoy.

Extract from Twentieth CenturyImpressions of Burma, 1910

On the 5th of January, 1915, Mr. A. C. Martin and his partner, Mr. DePaulsen, received a one year prospecting license from the government for an area in the Paungdaw region, Burma. They were interested in the extraction of wolfram.

The men went ahead with exploration and invested in excavations and buildings to deal with the wolfram they found on the 766 acre site. All was going quite well until they realized that they could not continue to renew and hold the license as neither was a British citizen. Like many British subjects in India (as Burma was still considered part of Bengal then) Mr. Martin was anxious to apply and receive the benefits of the Indian Naturalization Act of 1852, which allowed some who could prove they had lived most of their lives in a British colony to receive a British passport. Quite a few naturalizations had been granted to Armenians born in Persia but now living in India. Many of his friends such as the Manooks had received theirs with no problem. The case of Mr. DePaulsen was not as strong, though, as he was a citizen of Denmark and had been in the country only a few years. In Nov. 1915, Mr. Martin instructed his lawyer to apply for his and Mr. DePaulsen’s naturalizations. “Memorials” or affidavits were sworn by both men and although Mr. DePaulsen’s case wasn’t strong, Arrakiel Carrapiet Martin’s was. He had been in India for 40 years, had never been back to Ispahan where he was born, had property in Mandalay and Rangoon and had built up several businesses in Burma. He was confident he would get his naturalization.

The first few papers in the file seemed to agree with this.

From the Senior Registrar, 27. 12. 1915:

“There seems no good reason for reconsidering Mr. DePaulsen’s case and drafts saying so may be put up.

2. Mr. Martin on the other hand was born in Persia but appears to have lived in India nearly all his life. I think (sic) may get a certificate.”

From the Chief Secretary, M. Keith, 30.12.15:

“I know nothing about Mr. Martin, nor has F.C. [Financial Commissioner] sufficient information to justify an opinion on the desirability or not of naturalizing him. I suggest that the D.C. Tavoy [District Commissioner of Tavoy] be asked to state his opinion. I agree that there is no reason for reconsidering DePaulsen’s case.”

Even as late as 1.1.1916, another civil servant reiterates this advice, mentions Mr. Martin’s long service with the Public Works Department, the fact nothing is known against him in Rangoon where he lives and that he doubts the D.C. in Tavoy knows anything about him.

“The matter seems to be one of principle as other Persians are being given certificates at the present time. As A.C. Martin is a Persian only by name and has lived in India since 1895 when he was 10 years of age, [actually he moved to India in 1875] never returning to Ispahan and has worked for 15 years in the P.W.D. he seems to have a strong claim in equity to be naturalized. I submit a draft telegram….. if it is considered necessary to consult the D.C.”

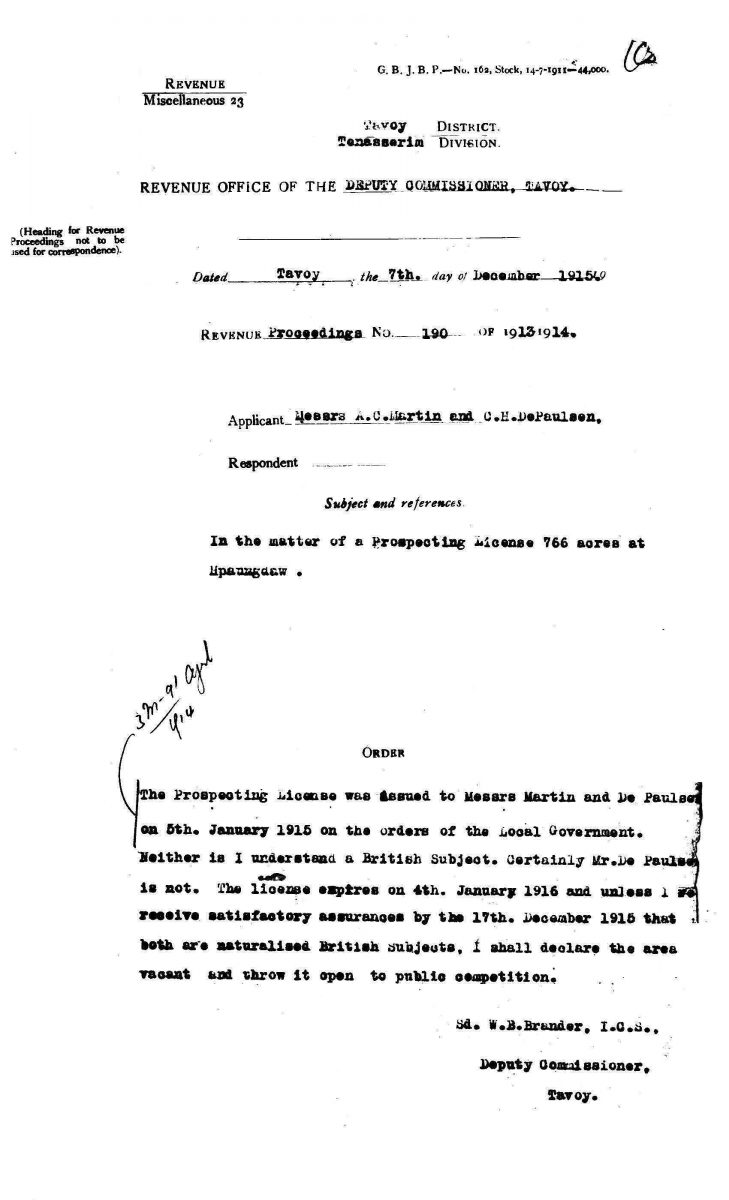

Far from the D.C. in Tavoy, a Mr. W.B. Brander, I.C.S., not knowing anything about Mr. Martin, we see a letter he sent on the 7th of December to Mr. Martin and Mr. DePaulsen, one week after their lawyer asks for them to be naturalized. He asks to be assured of their naturalization by the end of 10 days or the area will be declared vacant.

Letter from the D.C. in Tavoy

The last sentence is the whole point of the letter:

“I shall declare the area vacant and throw it open to public competition.”

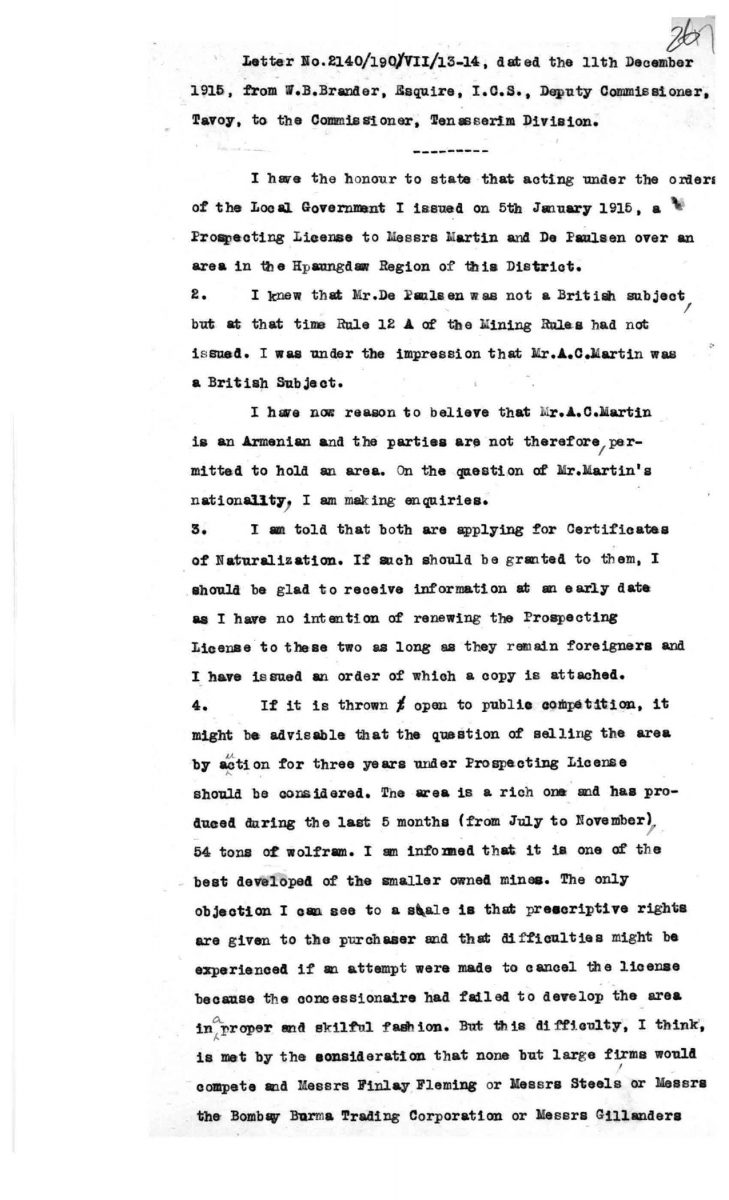

Why would he want to declare an area vacant that is being successfully worked for wolfram? Here is the letter Mr. Brander, D.C. Tavoy sent a few days later to the Commissioner of the whole area, the Tenasserim Division. In it he describes how rich the area is and how 54 tons of wolfram was produced in five months. He also points out there was nothing against granting a license to a foreigner at the beginning of 1915 as “Rule 12 A of the Mining Rules had not been issued.”

A gem from this letter:

“Item 3: I am told that both are applying for certificates of Naturalization. If such should be granted to them, I should be glad to receive information at an early date as I have no intention of renewing the Prospecting License to these two as long as they remain foreigners and I have issued an order of which a copy is attached.”

And the final kick is – he suggests the refused license could then be sold to one of the large British companies; not a small one because you need a large company to be sure to develop it properly (conveniently ignoring the success of Mr. Martin and Mr. DePaulsen over the year):

“…..none but large firms would compete and Messrs Finlay Fleming or Messrs Steele or Messrs The Bombay Trading Corporation or Messrs Gillanders and Arbuthnot are not the class of firm which could take up an area of this kind without putting every effort forth to make of the business a success.

As possibly a lakh or two of rupees might be credited to Government if my suggestion is adopted, I think it merits consideration.”

The Financial Commissioner immediately sent a telegram to the D.C in Tavoy, asking him to get a geologist out there as soon as possible and report back.

A year of extremely hard work establishing the wolfram mine was for nothing. The naturalizations of Mr. Martin and Mr. DePaulsen were refused. The irony of a xenophobic official, living in a foreign land, who had an abhorrence of “foreigners” was not lost on me as I pieced this story together. And all to preen his feathers in front of his bosses by earning them a few lakhs of rupees (see below for the conversion and what happened to Mr. Martin.)

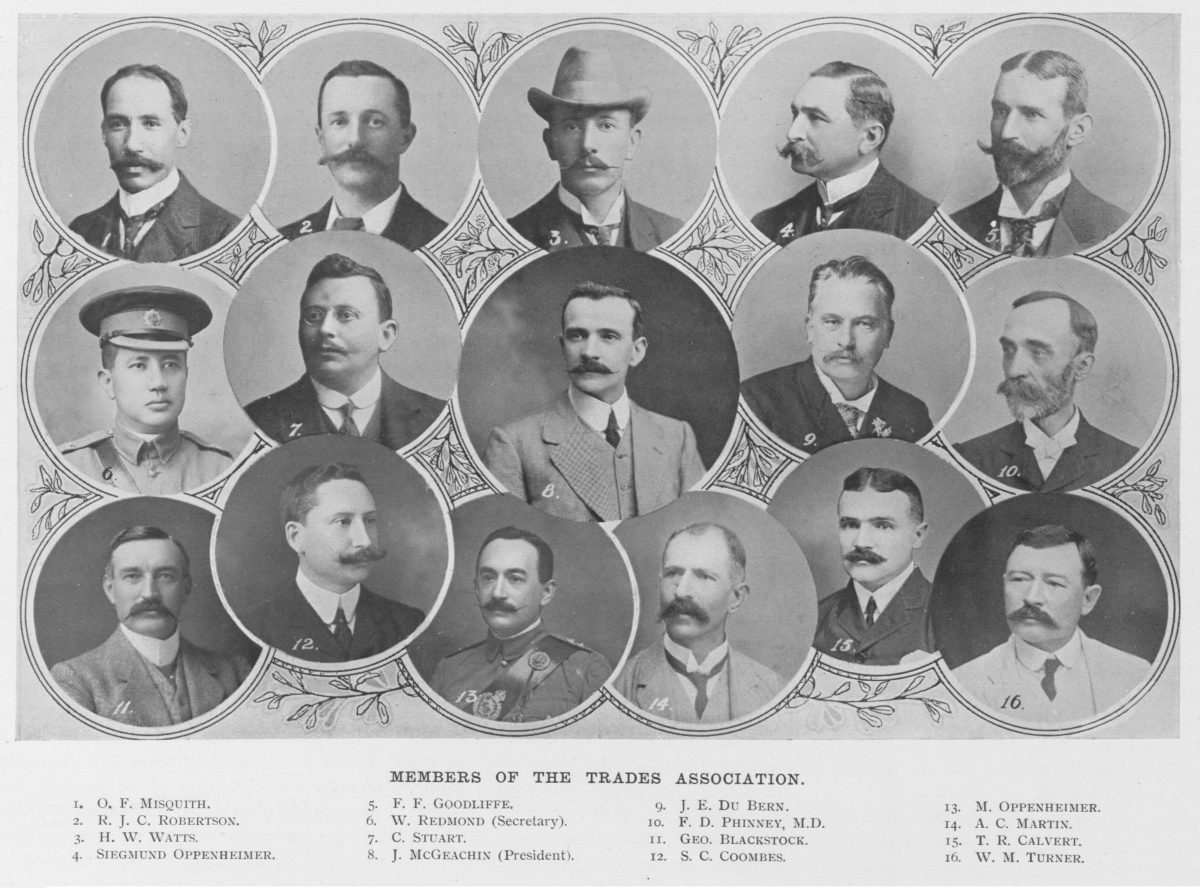

Members of the Trades Association, Rangoon 1910

From Twentieth Century Impressions of Burma

A.C. Martin is in the lowest row, # 14

- A lakh is the amount of 100,000. In 1916 the rupee was worth approximately US$0.31. So the first three year license at a minimum of three lakhs rupees would have netted the government about $93,000.

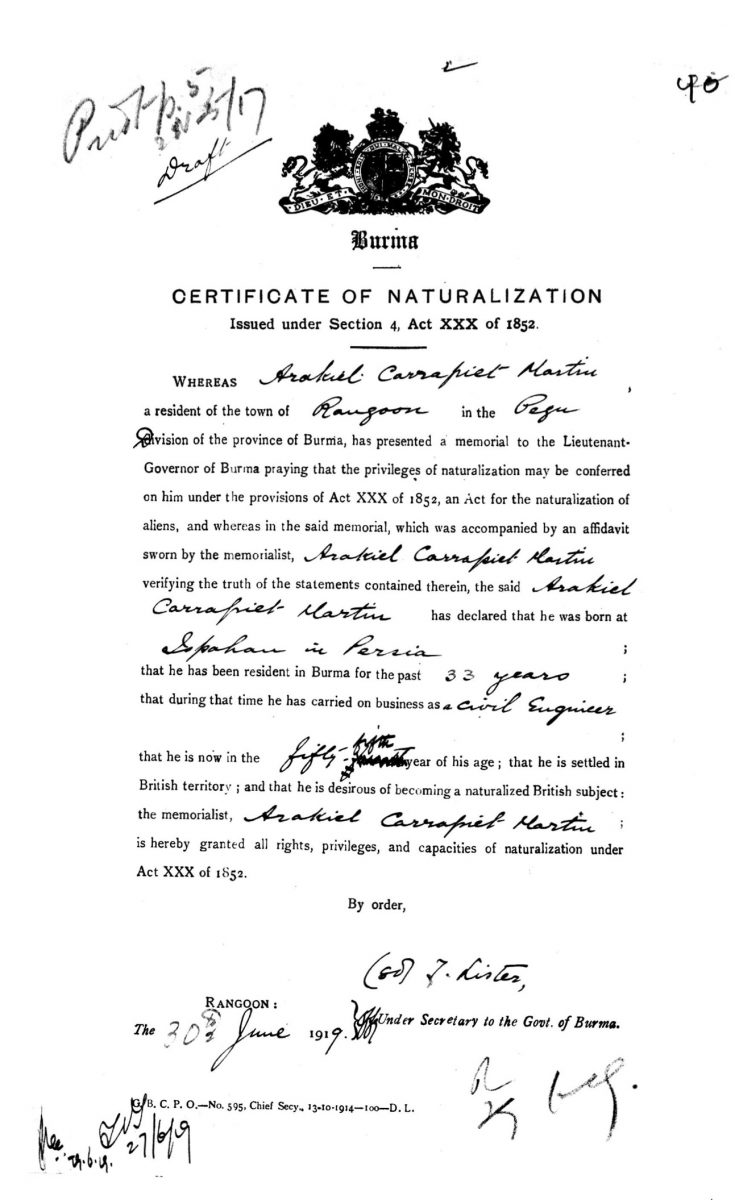

- In 1919, Mr. Martin applied for naturalization, after a failed attempt in 1917. The string of papers noted he did not get his naturalization in 1917 because of it being “undesirable to naturalize aliens during war.” The 1919 application was looked at favourably because of his long services to Government. At the time he was building a ship called the S. V. Armenia, the largest sailing vessel ever built in India. It was built entirely by Burmese labour and fitted out with teak. It was within days of launching, he had been offered and refused 5 lakhs rupees for it, yet he could not register it at Lloyd’s for insurance because he was not a British subject. The local government refused according to “the rules at present” but his case was then sent to the Government of India to decide. Finally, on the 30th of June, 1919 Mr. A.C. Martin was granted his naturalization.

A.C. Martin’s Naturalization Certificate. June 30, 1919

His firm also built the Rangoon Development Trust Building (now Department of Housing and Urban Decelopment) and Scott Market (now Bogyoke Aung San Market).

Thanks for that information. The Scott Market was built afterwards, in the 1920’s, and is one of my favourite places to go in Yangon. It is such a labyrinth that I never seem to find the sane shops from year to year, or maybe they come and go. I don’t know the other building, so will seek it out next month when I’m there.

Sharman

Walking the streets is so much more meaningful when you have the history!

Totally agree!

From Frontier Myanmar article about the redevelopment of the Bawdwin Silver Mine. A.C. Martin discovered it in 1900.

“Bawdwin: A 600-year history

Early 15th century: Chinese workers begin mining for silver to meet soaring demand in China, where uncoined silver was replacing government-backed currency in transactions.

1868: The Chinese owners and operators flee amid the Taiping rebellion and the Konbaung dynasty based in Mandalay takes control of Bawdwin. However, kings Mindon and Thibaw are unable to revive mining and smelting at the site before the dynasty’s fall in 1885.

1900: Railway contractor AC Martin claims to be the first Westerner to visit the mine. He tests slag heaps from earlier operations and estimates high levels of lead, zinc and silver.

1903: The Great Eastern Mining Company, registered in London the previous year to develop the Bawdwin deposit, starts building an 80-kilometre narrow-gauge railway from Bawdwin to the Mandalay-Lashio line to transport the slag.

1904: Future US President Herbert Hoover, then a mining engineer, hears about Bawdwin from AC Martin, who is a Great Eastern director.

1906: Hoover forms the Burma Railway and Smelting Company (later Burma Corporation) and buys out the financially stricken GEMC.

1909: The railway line is finished and mining begins by reopening the Dead Chinaman Tunnel.

1912: Smelting operations are shifted from Mandalay to Namtu.

1913: The silver-rich Chinaman lode, estimated at 180 metres long and 20 metres wide, is discovered.”

Read the full article here: https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/fluctuating-fortunes-at-the-bawdwin-mine

Dear Chasing Chinthes,

I am a Masters student at Northern Illinois University (United States) working on my thesis related to colonial photography in Burma/Myanmar. Your digital collections has images that I am interested in using for my research, which will be submitted to the graduate school but not published for commercial use.

Am I allowed to use your images for this purpose? Are the photographs out of copyright now and available for me to use on my thesis?

My thesis will focus on the works of D.A. Ahuja, Philip Klier, and Felice Beato. Your collection’s postcards are of most importance and would serve great use for my research.

Please advise.

I’ve sent you an email.

Sharman,

Your article on A. C. Martin was most interesting. I believe that his partner, Mr. C. H. DePaulsen, may have been the father of Peter DePaulsen, a railway engineer, based in Insein prior to and after WW2. I’ve forwarded the article on to the DePaulsen family for confirmation.

Re. the Bawdwin Mine in Namtu, it appears to have been in production for some 700. I’ve included an excerpt from an article that I wrote a few years ago about the exploits of Patrick “Red” Maddox of SOE and OSS fame during WW2 in Burma. He blew up the Bawdwin mine to prevent it from falling into the hands of the invading Japanese Army.

I’d be interested in any further information that you may have.

Regards.

John Mealin

Excerpt from John Mealin’s article on Patrick “Red” Maddox:

Bawdwin mine – built by a future US President

According to Chinese literature, they were the first people to work the outcrops (exposed bedrock on the mountain ridge) in the 12th century. The silver generated considerable wealth to the Chinese rulers for 700 years. Some of the old workings including the bamboo supports were still being found 200 feet underground.

The Chinese miners left behind hundreds of slag piles, mainly litharge (a natural form of lead oxide), after the silver had been extracted. These had accumulated over the mountainside over the centuries. In time, the slag heaps would yield large tonnages of metallic lead to be exploited during the 20th century.

Between 1851 and 1906 mining stopped in Bawdwin, until a professional mining engineer, Herbert Hoover, visited the site. He recognized a major investment opportunity.

Yes, it was the same Herbert Clark Hoover who in 1929 became the 31st President of the United States.

Hoover traveled back to England where he had no difficulty raising the investment funds for a new corporation, Burma Mines Limited. In 1908 the Bawdwin mine went into production. He initially acted in an advisory capacity, eventually taking over operations and management in 1913. In due course, it became one of the foremost global mining operations. During his stay in Burma, he maintained an office in Mandalay.

Burma Mines built its own narrow gauge (2 foot) railway connecting Bawdwin with Nam Yao, 42 miles away, a Burma Railways junction on the Mandalay – Lashio branch. This was its first major capital expenditure. The mine also contained an electrified underground railway with 100 hopper cars.

By the time Hoover resigned from the Board of Directors in 1918, the Bawdwin mine was a major success. It contributed significantly to the $4 million he had accumulated, an absolute fortune in those days. In 1919 Burma Mines Limited was acquired by Burma Corporation Ltd., a British company with headquarters in Rangoon.

A Perilous Mission in 1942

At first glance, the Bawdwin-Namtu mission looked straight forward – Red would slip in unobserved, lay the demolition charges and escape swiftly. In reality, it was anything but that. The mission was fraught with danger.

In April 1942, the Japanese army had reached Lashio, 42 miles south east of Bawdwin-Namtu. They were well aware of the British “scorched earth policy”, with the Mawchi mines blown and the Yenangyaung and Chaulk oil fields and Syriam oil refinery destroyed.

The Japanese knew that the Bawdwin-Namtu mine facilities were next on the British “destruction” list. The enemy soldiers and renegade natives would now be on the look out for British army infiltrators.

The area that Red had to infiltrate was heavily wooded, mountainous country with deep cut ravines. Navigating through the woods and up and down the steep hills would be grueling. Unfortunately, there was only one road in and out which, without doubt, would be closely watched.

To make matters even more menacing, Red’s strategic targets were wide-spread. The mines were in Bawdwin, 12 miles north-west of Namtu. The administrative offices, lead smelter, mill, blast furnaces and roasters were in Namtu. The hydro electric power station was on the Mansam Falls, 28 miles south-east of Namtu, on the Nam Yao River.

Red had to find his way into each location without being detected. He then had to set his demolition charges where they would do the most damage. His concern was with the integrity of the pencil detonators that set off the charges. They were generally reliable. However, he had been warned that they could go off prematurely, as Red was to experience on a future mission with the OSS. He needed them to work perfectly, detonating only after he had set charges at all locations and was well clear of the territory.

There was only one way to penetrate the area unnoticed — in disguise, dressed as a Shan native. It posed the least risk of detection and the best likelihood for success. This was his first vital mission. He had been trained intensely by some of the best instructors at the SOE. He knew his life was on the line!

Before Major Lindsay left to destroy the Mawchi mine in the Southern Shan States, he had arranged for the cache of arms and explosives stored in Maymyo to be transported to Myitkyina for distribution to the Northern Kachin Levies. What is unclear is whether Red was responsible for this delivery.

The route the transport took was from Maymyo to Lashio to Bhamo and then on to Mytikyina. What we do know is that the arms and explosives that Red used for the Bawdwin-Namtu mission originated from the cache destined for Myitkyina.

Bawdwin-Namtu is 42 miles north-west of Lashio. Red’s journey to the mine would have taken him close to Lashio. It was a perilous journey but he got to the mine safely, where he laid his first batch of charges.

There were a number of facilities to be destroyed at Namtu including the smelter, mill and blast furnaces. Red laid his charges, set the timers and then continued on his way to the Nam Yao River, 28 miles to the south-east. There, at Mansam Falls, he laid more charges at the hydro electric power station.

Red lived up to his reputation of “getting things done right”. His sabotage mission was a complete success. Bawdwin-Namtu was put out of business.

In November 1951, the Burmese Government was still trying to figure out how to get Bawdwin-Namtu back into production. No new ore had been mined at Bawdwin since April 1942. The explosive damage to the facilities and the subsidence at the mine put it out of commission for the duration of the war.

Hidden Treasure

Treasure still lies hidden under a rock in jungle near Namtu (Northern Shan States)

After immigrating to the UK, Red sometimes spoke of going back to Burma to dig up the buried silver. His family thought it just a joke, not knowing the full story behind it.

Quite independently, Michelle Melson recently indicated (2014) that her grand-aunt’s brother had met a Bawdwin mines’ employee in New Market (Calcutta), shortly after he had trekked out from Burma to India. He spoke about the buried bullion, indicating that it still lay hidden somewhere near Namtu under a rock in the jungle. Michelle’s great grandfather (Michael Melson) had also worked at the Bawdwin Mines. Apparently, he perished whilst escaping the Japanese on the horrendous trek to India.

The Burma Corporation tried to locate the silver after WW2 but those who knew the location offered no help. The Shan States were in political turmoil following the controversial 1947 British agreement with General Aung San. There were too many insurgents around and it just wasn’t safe to go back. The key to finding the treasure lay in the memories of those who helped bury it. And now, after 70 years, they too are long gone.