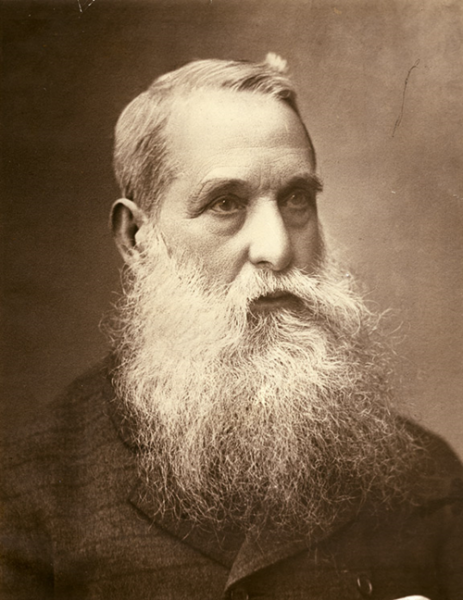

Capt. Linnaeus Tripe

Linnaeus Tripe was born in Devonport, Devon on April 14, 1822, the ninth of twelve children. His father Cornelius was a surgeon. In 1839 he joined the East India Company as an ensign in the 12th Madras Native Infantry, and travelled to Madras on the Carnatica, a voyage of four months. He was promoted to lieutenant early in 1840 and followed the usual round of moving to different posts in India with his regiment. In November, 1850 he sailed back to England (a five month journey this time) and arrived at a momentous time in its history: a celebration of the midpoint of the century with the the Great Exhibition of 1851. It was a fortunate coming together of circumstances that would change his life.

The daguerrotypes of the Americans and the calotypes of the French won awards and there were many photographs displayed throughout the Exhibition, as well as camera equipment and supplies. He must have been fascinated by this new technology, for at the end of 1851 he placed an order for equipment with G. Knight & Son and by early 1853 he was elected a founding member of the Photographic Society of London.

Although we don’t know the precise make of his camera, we do know it took 12 by 15 inch negatives which meant it was one of the more advanced options of the time. He used waxed paper negatives which were easier to carry and develop than the usual glass plates. We do know his lens was the four and a half pound Ross No. 4 Landscape Lens, with a focal length of 20 inches.

Unlike many new photographers he eschewed the taking of sentimental and highly narrative scenes in favour of an architectural approach to his subjects of ships and dockyard paraphernalia. His eye for composition was well developed by the time his leave finished and he sailed back to India in April of 1854.

Quarterdeck of HMS “Impregnable,” 1852-1854

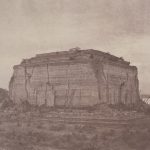

At the end of the year he took leave and self financed a photography expedition to Mysore where he used his meticulous method of long shots, mid-shots and close-ups to document two temples. Always aware of light, he employed it to advantage on complex carvings and to enhance his depth of focus. He entered sixty eight of these photos in to the Raw Products, Arts and Manufactures of Southern India exhibition and won a First Class Medal in 1855.

Hullabede: Temple of Siva, Sculptures, December 1854

This honour brought him to the attention of Lord Dalhousie, the governor-general of India, who was planning a political mission to the King of Burma after the Second Anglo-Burmese War in 1852. The British wished to explore and record as much as they could about the country and so hired Colesworthy Grant as the official artist but also Tripe as the photographer for the mission. His was the first such appointment given to a photographer in the history of British diplomatic missions.

Tripe threw himself into preparations for the trip. Specially made sturdy and waterproof cases were ordered for all his equipment and supplies, including the waxed paper slides and the developing chemicals. He even included a small still so he could be sure of using only pure water when fixing the negatives. He left Bangalore in July 1855, headed to Burma by way of Madras, Calcutta and the Bay of Bengal.

The Mission to Ava sailed upriver from Rangoon on August 1, 1855, under the leadership of Col. Arthur Phayre. Tripe started taking photographs once they reached Prome (now called Pyay) and numbered them sequentially.

No. 2. Prome. North entrance to the Shwe San-dau Pagoda

We do not know how he worked, whether he had an assistant or what happened day to day as he left no diary. There is a scribbled note found later which gives us some idea of his difficulties:

“he was working against time; and frequently with no opportunities of replacing poor proofs by better,” and “from unfavourable weather, sickness, and the circumstances unavoidably attending such a mission, his actual working time was narrowed to thirty-six days.”

It is on record that of 6,517 prints 2,832 had to be rejected, and that many plates were ruined because the heat melted the wax on the negatives. Considering that temperatures in the months of August, September and October in the Dry Zone of Upper Burma regularly exceed 40℃ (100℉) his accomplishment was astonishing.

![No. 9. Ye-nan-gyoung [Yenangyaung]. Balcony of a Kyoung](http://www.chasingchinthes.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/No.-9.-Ye-nan-gyoung-Yenangyaung.-Balcony-of-a-Kyoung-600x446.jpg)

No. 9. Ye-nan-gyoung [Yenangyaung]. Balcony of a Kyoung

![No. 10. Ye-nan-gyoung [Yenangyaung]. Tamarind tree](http://www.chasingchinthes.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/No.-10.-Ye-nan-gyoung-Yenangyaung.-Tamarind-tree-600x445.jpg)

No. 10. Ye-nan-gyoung [Yenangyaung]. Tamarind tree

It took him two years to complete the printing of a book, “Burma Views,” of which 50 copies were sent to the government in Calcutta in March of 1857, along with all the other prints, both partial and complete, that he succeeded in making. The government was so impressed with his work they granted him the copyright on all the images and gave him permission to make them for himself and for retail.

He was also given the office of photographer to the Madras Presidency which lasted until the end of 1859 when a newly appointed governor, Sir Charles Trevelyan asked whether the “Photographic Establishment is not an article of high luxury which is unsuited to the state of our finances.”

One can only believe that this was a blow of huge magnitude to Tripe, because of his subsequent actions, or rather omission of action. After putting on the pressure to finish printing all the work he had taken in Madras, while contending with constant requests for updated reports and financial scrutiny, and dismantling his printing studio, he returned to England on convalescent leave in the spring of 1860. He took no photographs while on leave.

Not a rich man, he was forced to resume his army career in India in 1863, where he remained for ten years. He took a only a handful of personal photographs of Burma in that time. Compare this paltry output with the impressive production during a single visit of three months to Burma on the Mission to Ava and a subsequent six months in 1858 travelling around India – 794 negatives.

In 1873 he retired to Devonport and never took another photograph. He died in 1902.

- Capt. Linnaeus Tripe

- Quarterdeck of HMS “Impregnable,” 1852-1854

- Hullabede: Temple of Siva, Sculptures, December 1854

- No. 2. Prome. North entrance to the Shwe San-dau Pagoda

- No. 6. Thayet Myo. Pagoda on the S. of Cantonment

- No. 9. Ye-nan-gyoung [Yenangyaung]. Balcony of a Kyoung

- No. 10. Ye-nan-gyoung [Yenangyaung]. Tamarind tree

- No. 25. Pugahm Myo [Pagan]. Carved doorway

- No. 36. Tsagain Myo [Sagaing]. Water Pots

- No. 44. Amerapoora. View at N. end of the Wooden Bridge

- No. 46. Amerapoora. Colossal Statue of Gautama close to the North end of the bridge

- No. 52. Amerapoora. Mosque

- No. 57. Amerapoora. Street in the Suburbs

- No. 96. Mengoon [Mingun]. Ruined Griffins

- No. 97. Mengoon [Mingun]. Pagoda from North West

- No. 100. Rangoon. Patent slip

- No. 101. Rangoon. A Street; old Style

- No. 102. Rangoon. Signal Pagoda

- No. 106. Rangoon. View near the Lake

- No. 108. Rangoon. South Entrance of Shwe Dagon Pagoda

Please click on the photos for credits. Quotes and information taken from the book “Captain Linnaeus Tripe; Photographer of India and Burma, 1852-1860” by Roger Taylor and Crispin Branfoot with Sarah Greenough and Malcolm Daniel.

Sharman, have just got to your info. re Linnaeus Tripe. A volume of his work is available on the open shelves at the BL in the Oriental/African Room (top floor). I looked at it hoping to find portraits but he seems to favour buildings, statues etc. I got to your site by accident as my e-mail has an error. Lolve from Richard Carlyon.