Quite a few years ago I was contacted by a man who had some First World War medals and “some letters and documents” he wished to sell. At that time I would take items on consignment and sell them on eBay. I visited him and through this informal archive learned about George Roderick Chisholm of the Canadian Infantry’s 78th Battalion, and his short life in WWI.

After choosing the most interesting passages from just George’s letters, there were over 5,000 words of quotes – far too long for a blog, I thought. How do you do justice to any person’s life from a hundred years ago, let alone one who fought in The Great War, without making it a long read? You can’t. So, in honour of the memory of Pte. George Roderick Chisholm, most of the talking will be done by his correspondence with the family, the letters of others and selections from his war records and other documents.

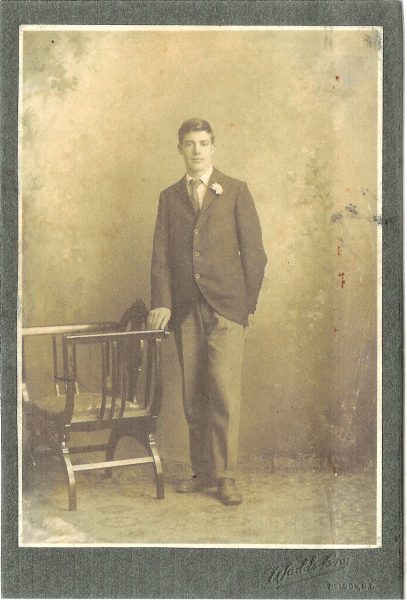

George in his bank clerk suit, ca 1914

The Chisholms were an old family from Nova Scotia. George, born March 15th, 1897, in Pictou, was the youngest son of five children and by the 1911 Census the family was living in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. George started work as a clerk at The Royal Bank of Canada in Saskatoon on July 2, 1914, following in his father’s footsteps. He later transferred to Nelson, B.C.

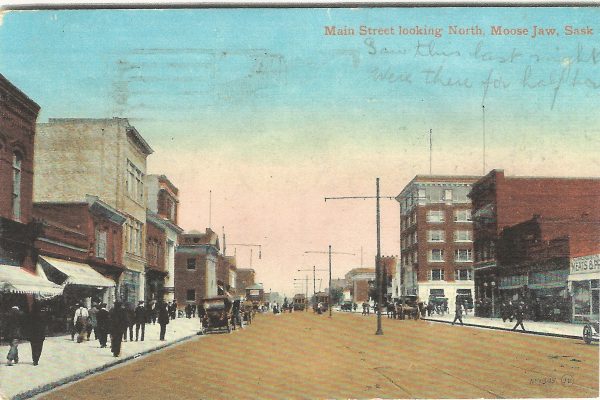

Postcard from Moose Jaw sent as he made his way to Nelson, B.C. for his job at the Royal Bank.

Reverse of card

His older brother, Cyril, had already enlisted in 1915 in Lord Strathcona’s Horse, and perhaps George felt he wasn’t doing his duty by working in a small town bank branch. Just before he left for France, Cyril wrote on Jan. 1, 1916:

Cyril Chisholm

“Tell George to stay where he is and if he has any sense left he will.”

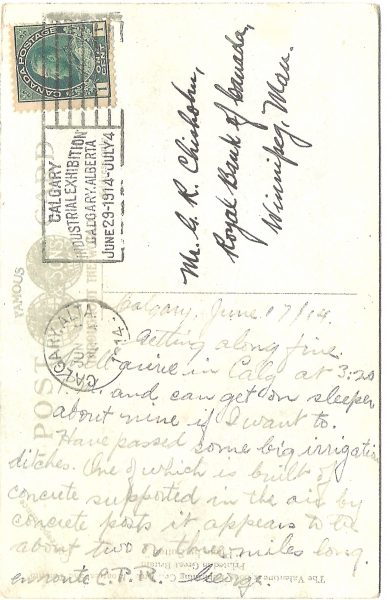

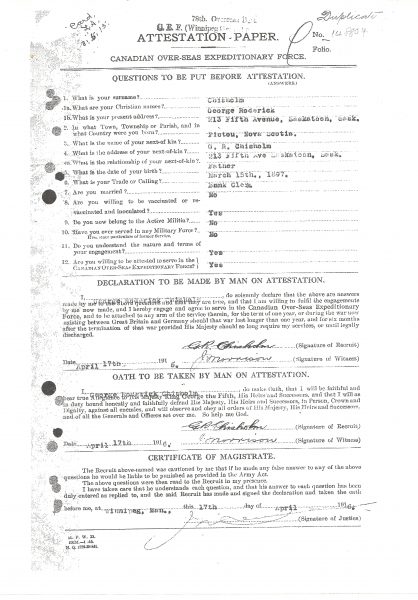

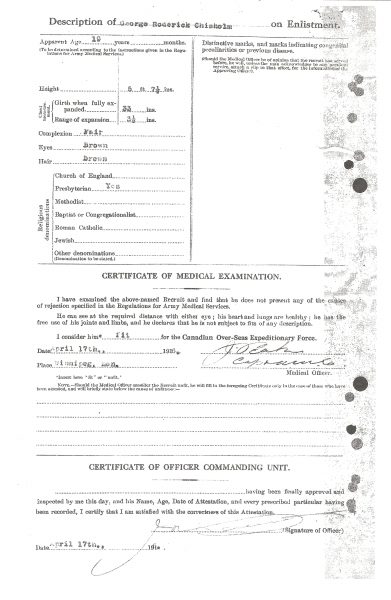

True to all younger brothers, George didn’t listen. His attestation papers show he enlisted on April 17th, 1916, when he was nineteen years old. In Winnipeg he joined the 78th Infantry, C.E.F. for preliminary training.

Attestation page 1

Attestation page 2

A group of unnamed soldiers in the 78th Infantry, 1916

May 13, 1916, Winnipeg

Today I am sending a picture of the battalion but you will need a microscope to see me with. I have marked the place. I am also sending a pin to each of the girls. The little maple Leaf is for Annie (the one on the pin). The gilt bursting grenade for Gladys and I will try to get a larger one for Bird in the semi-khaki color the same as we wear in our hats but may not be able – our canteen haven’t any left. The one I am enclosing is for you if you would like to wear it as a buttonhole – it is more or less a fixture but is exactly what our hat ones are like. The pin is intended to give away and the one with fasteners for wearing ourselves.

Received the music from Bird today. Thank her but tell her I only intended to get my own old stuff and not that she should go to the expense. However, I am much obliged and will take them with me as there will be a piano somewhere.

The 78th button Battalion pin mentioned in his letter

Shortly after this letter the battalion were off to Halifax for embarkation.

On the train to Halifax:

At all the larger towns we had quite a number at the stations. Every day at division points we got off for route marches through the main streets. On Sunday we (the 78th) had to parade in the big street parade – it was some length. We were at the head of the infantry section and when the one end was at the cemetery, the other was just passing the Royal Alex. That would be the same as two ranks packed solid for about three miles.

SS Empress of Great Britain

We arrived in Halifax on Saturday 20th and didn’t leave till Monday morning but of course we were put on board and the transport went out in midstream to anchor so there was no chance of seeing anything more of the relatives.

The Seventy-eighth have the best quarters on board and are the senior battalion. Base Co. is quartered on “D” deck and parades on “A” so we are alright.

Monday, May 29th, 1916, Liverpool

Tonight just at seven the ship pulled into port. Every few minutes along comes a small boat load of people just to wave and cheer. Well, reveille is 3:30 am tomorrow and I haven’t gotten over my guard night so am feeling a bit blue.

I forgot to say that I am and have been smoking since leaving the Peg.

Has he indeed? That’s not all. His records show he was confined to barracks (CB) at the training camp in England for eight days, for gambling. See the second entry below.

24-6-16 Gambling in lines – 8 days CB. (c. LAC)

This is how he describes the CB in his next letter home:

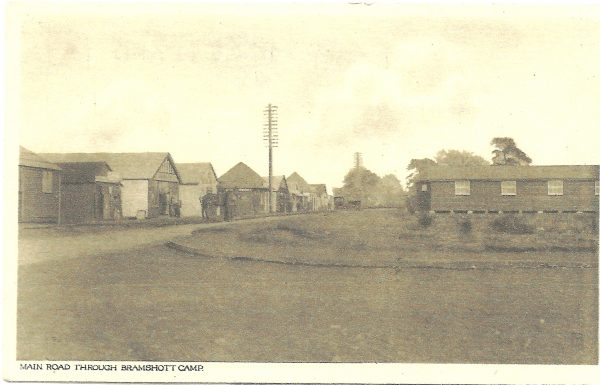

June 25th, 1916 Bramshott, Hants

Quarantine is very exciting.

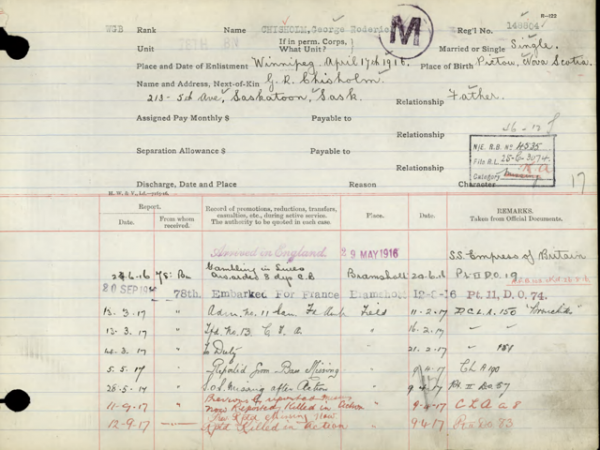

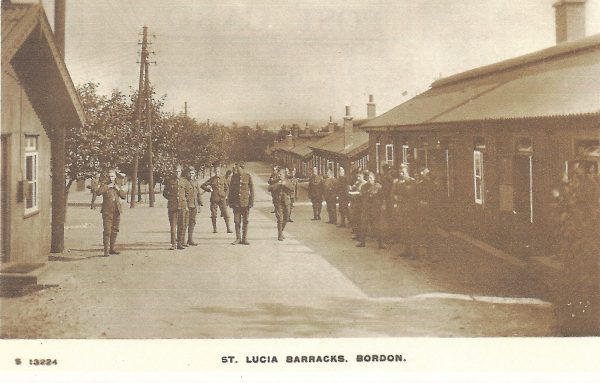

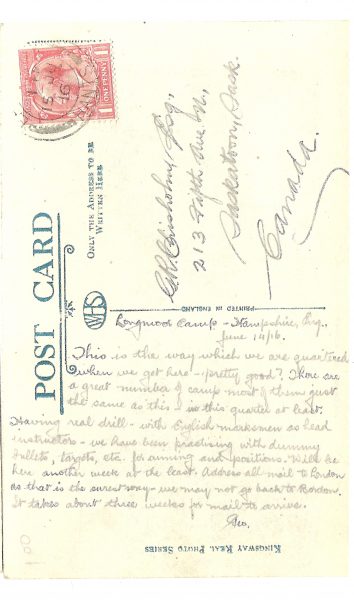

You will have received the cards of Bordon ”huts” and “parades” by now – here the huts are not so nice to look at but are on the same plan and will be fine for the summer. Just a couple of days and the seven of us will be free to go and come with the rest.

Bordon camp 1916

Reverse of postcard from Bordon

We know George was musical and could play the piano. In his first letter after joining up he thanks his sister, Bird for the sheet music and expects there to be a piano somewhere. The letters below show what lengths (literally and figuratively) he will go to to satisfy his urge to play.

July 16, 1916 Bramshott, Hants.

Am awfully glad to get the parcel – it sure goes right to the spot everything was all that I could want and I don’t know what I thought the most of but the home-made cookies surely were “it.” You cannot buy home-made stuff that is worth eating. I have tried some pies – talk about country pies – dough inches thick and only half-baked.

St Stephen’s Church, Liphook Road, Shottermill

On Friday the Battn was on a twenty mile march all day. I was not so tired that I couldn’t go another three and back for an organ practice. The organ is run by a pump and I have to get a kid to work whenever I go down (Shottermill) again on Saturday afternoon I was at it again for two hours. The organ is only a one manual with pedals of course and only eight stops so there is very little to get confused with.

July 23, 1916 Bramshott

Today on our dining room fatigue washing tables, floor, etc. after each meal, I can still smell the mush (porridge) on my hands from breakfast, and they look like goose flesh from the soda in the water.

Nearly every night I go down and practice – have to get a kid to blow for me which costs the immense sum of 12 cents the lesson of a half hour – amounts to one shilling once a week- isn’t that enormous. Last week Mrs. Robertson sent a box of tarts (fine!) to me unfortunately they were in a paper box and the tarts were as flat as pancakes but unharmed as they were a pineapple centre and weren’t mushy.

The Mrs. Robertson mentioned above was the wife of Lieutenant-Colonel Struan Gordon Robertson, born in Scotland but now from Pictou, N.S. The families may have known each other socially or perhaps the Lt.-Col. felt responsible for his Pictou boys. In any case, he and Winnie Robertson entertained George in England and treated him like a son, as we see in the long excerpt below. George is exposed to his first displays of snobbery of the “Imperialists” over the “Colonials”, but stands up for himself.

Bramshott Camp

Aug. 2, 1916 Bramshott

For example – we have a rotten major in many ways. Always looking for all the smallest of faults – a frequent sentence – Cover off no matter the conditions while he rides a horse we have a pack, rifle and walk. Today we were kept on the go – route march – until quarter to one – oh the sun was hot. When we arrived at our destination (12 or 15 miles) we all got to the shady side when along comes Maj. and says “ fall in.” As soon as we were back up and had our coats all buttoned up he said, “Fall out.” It was so ridiculous that the whole company laughed at him (227 men.)

Last Friday evening a quarter of the Battalion got leave till Monday midnight. I was one of the lucky ones. We (200) stood till 8 P.M. and 10 P.M. from 4:30 waiting for transportation tickets – there were several (many hundreds) going on leave at the same time. I got off on the first train out. [to London]

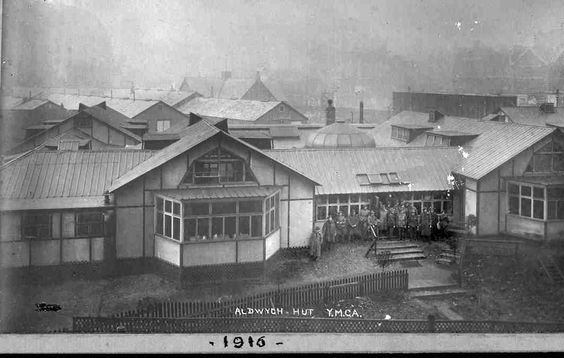

Then we hunted up a “Tube” and as it was too roundabout took a bus and went to the “Y” Aldwych. It takes some describing.

The Aldwych YMCA Hut, London

Copyright Harold J. Curnow

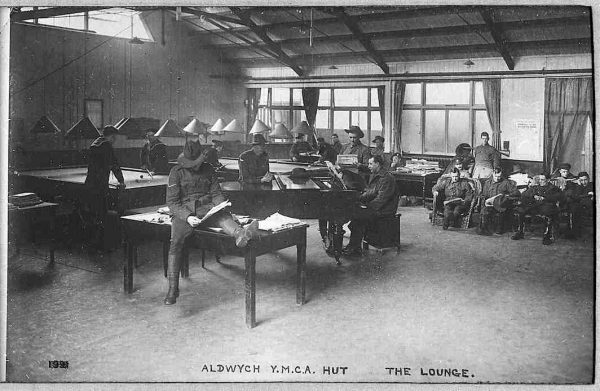

The Hut was ideal in many ways – three or four chesterfields – leather and a couple of suites of leather chairs so comfortable etc. A grand piano, Victorola and billiard tables – baths, beds in either cubicles (one above the other, two per room) or a private room (one bed). The rooms are of course just enough room for the beds and a chair (150 beds in the Aldwych). Then there is a café where you can get a meal at cost (very little) served at any hour (all night). The women serve all the time. The “Y” of course is in great demand, and the second night I couldn’t even get a camp bed but that comes at another time. The first night I had a camp bed in the billiard room.

Copyright Harold J. Curnow. Picture taken by his fatherJ.J.Percival Curnow, who was in charge of the YMCA Aldwych starting in 1914.

(The next day he had dinner with the Robertsons and declined their offer of a bed.)

There was such a crowd of soldiers in town that I couldn’t get a bed anywhere after walking till 1 A.M. so went back to the Aldwych Hut and slept on a mat with the majority of my clothes on.

The next evening he is back with the Robertsons again and gives his opinion of the young couples he sees.

The R’s took me for a stroll along the Thames which is very much like our Assiniboine at that point and like the Red near the Tower. There were any number of punts on the river, all flat bottomed and something like a long rowboat. Any number of soldiers and civilians and women, of course, and they were all at the same game – the fellow with his arms around the girl – In one scene there were two pairs – disgusting out in such a place.

Sunday night I had a bed in a cubicle – white sheets, pillow (the first I have seen since leaving)

He spends the better part of the following day with Mrs. Robertson, who takes him from the Abbey to St. Paul’s to the Tower in a taxi, and feeds him at every chance. They meet “Mrs. P.” an English friend of the Robertsons.

All the English people around London – whether they say it or not – have the idea we are just here to fight their enemies on their account and of course they have to be patronizing to us “colonials” that wear sheep-skin vests and clothing out West and very little better in the East or things of that sort as Mrs. P. had the nerve to say but we put her right.

The Crown Jewels were too amazing to believe, apparently.

The Crown jewels were all there but we are so unused to such sights several asked if they were imitation although they were in the Tower and in a glass cage with iron bars and every stone known throughout the Kingdom. We all had the impression, and although we were assured, I still am doubtful – crazy – one diamond was easily as big as the ring I have drawn here.

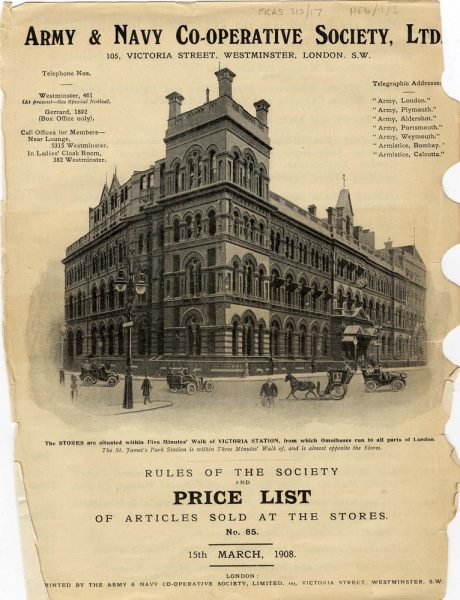

Well – lunch time – which Mrs. Robertson did at the Army and Navy Stores, where you have to be an officer’s wife or a large subscriber to the War Fund before you can buy anything. It was a swell departmental store and I was thoroughly out of place with my private’s outfit sitting down to luncheon. Officers, swells, etc. were the only ones there. Mrs. R. had some business at Lloyds (branch) which is in the Can. War Offices (Pay & Records branch). I was stopped when entering with her which was embarrassing for her But I didn’t notice it much myself (again the uniform.)

Army and Navy Stores, London from House of Fraser Archives

After his long weekend with the Robertsons it’s back to the training camp at Bramshott.

Had an easy day the Tuesday as I am on a bombing course although it is very broken up – Wednesday was much the same and Thursday we didn’t go out till 4 P.M. but we carried the pack we go to France with and it weighed between 80 and 85 lbs. and a rifle of 10 or 11 lbs. We had I pr boots, 1 undershirt, holdall which carries soap, brushes, etc., balaclava, housewife (needle, thread buttons, etc.) 1 pr laces, razor, towel, flannel shirt, 2 pr sox, knife, fork, spoon, 1 great coat, 1 entrenching tool, 2 gas masks, and 1 pr. Goggles, to keep the gas, which affects your eyes, away. Bayonet and 120 shells, loaded. It was awful and we were out for a 12 or 15 mile walk which took 5 hours. Bill fell out and I was all in but managed to stick it although my feet, shoulders, neck, legs and everything was sore.

In his last undated letter before embarkation to France he emphasises how he must keep locations secret and explains in more detail what makes up his kit.

Last letter before embarkation – Between Aug 7-12, 1916

The other day – the 7th– we were inspected by Lloyd George and Sam Hughes. The whole division (4th) were there and it took about three hours for the march-past. First, the 9th, 10th, 11th and then our Brigade (12th). There are 4 battalions to each and 4 Companies to each Battn. Besides transport teams at the end of each Battn and field kitchens – an ammunition mule for each Co. The movies took the whole show and as you may see it on the screen watch out for the fourth Battn. In the 12th Brigade and I the third (and last) company front rank just to the right of the major on horseback and as I am just a little taller as the boy on each side for three or four around you may see me –so take your specs. Well, so much for that.

It is quite plain there is no news. We leave Saturday for “somewhere” and should you like to know what we carry I will give you a list;

Cap – Boots – Undersuit – Tunic – Puttees – Pants X – Shirt (Khaki) – Sweater X – Braces – Identity Disc X – Badges – Sox – 4 field dressings (put into a place which we cut open in our tunic – Clasp Knife – Paybook – Harness, rifle and bayonet, entrenching tool, 120 rounds of ammunition, 2 gas helmets and a pair of special gas goggles (weeping gas). That we wear on ourselves. Everything new in the way of clothes I have marked with an X underneath [I have transcribed it beside the items].

In the pack we carry great coat, waterproof sheet, 1 shirt (I am taking a woolen one and wearing one also, Gladys’ Khaki one), 2 pr sox (I have 3) 1 mess tin. In our haversack we have 1 towel, Balaclava, housewife (razor, comb, soap, tooth and shaving brushes, mirror – metal sheet – a pair of laces, holdall (darning, needles, buttons, etc) and rations for the balance of the day. Believe me I am loaded down and if both Gladys’ and Bird’s socks had come I don’t know what I would have done.

Anything I may say must be absolutely secret or I may get into deep water as the censor may miss something. The whole lot of us are on the move – sixteen to twenty thousand, all Canadians. That seems public around here.

Should we get taken prisoner (don’t worry there won’t be any Bosche get me) and look out for my signature George R. if eats are wrotten [sic] or not enough and there won’t be any need to think anything is wrong unless I address to Papa and sign “Jr.” only.

Please do not send me any handkerchiefs or paper and go easy on sox for a while.

He leaves for the Front on August 12th, 1916 and docks in LeHavre.

Aug. 14, 1916, France

Everyone smokes – on the beach yesterday while waiting for a swim – “le petit garcon” came around in bunches and begged cigarettes – even those who could hardly “toddle” along – thinking the little ones didn’t smoke I passed him one and asked him “fumez-vous” – he was quite indignant and although I couldn’t understand him, his expression soon showed me, and then asked for “une allumette” and proceeded to light up.

Another kid tied a piece of the Belgian colors on my hat strap, so I will enclose it. They wanted anything – buttons, badges, pennies, etc. There is very little actual silver in circulation – we get sous and fifty centime pieces and francs but circulation is mostly paper- 50 centimes (10 cents) even is a sort of “shin plaster” affair as also the other denominations.

50 centime note, 1916

His letters from the trenches simultaneously recount the conditions and the casualties with reassurances to his dear Mama that he is in a “safe” position. He was in working parties that operated at night.

Aug. 27, 1916, Trenches

Next move was a long march to a “tent” camp where we had more or less time of our own but we had a couple of marches and the cobbled roads got my feet, awfully.

Next we had a long march to the reserve trenches and spent Saturday night there. We have seen a number of aeroplanes, only one of “Fritz’s” – ours come around in any number from one to twelve – that is the most I’ve seen in one squad. They are constantly being bombed and some were pretty above tonight. We had a “hit (?)” this afternoon and a couple of the “Imperials” had a narrow escape.

Our first night (night before last) while on a working party expedition one of our company’s boys was killed by a stray bullet. It was only one chance in a thousand – there is comparatively little danger on an outing such as this was and ours was less dangerous. The Germans use an awful lot of “star” shells. They light the country for about six hundred yards in all directions, just like a great electric arc.

Aug. 31 – We are safely at the base camp again. Rec’d cake etc. also Gladys’ box.

Canadian troops, wearing leather jerkins and trench waders, outside a coffee stall in the mud.

© IWM (CO 1030)

The “Front” he refers to is the Somme. The lack of proper communication and resultant misdirection took a heavy toll on the soldiers, both physical and mental.

Front Sep. 10, 1916

The first night we got to the wrong place and had a ten mile walk for nothing. Next day we were on Parade nearly as early as usual and off an hour earlier. That night we worked from eight thirty to three, got home at four A.M. and it was work. Next A.M. at 8:30 we had to tumble out for a five mile walk each way for a bath. They change the towels, sox, top shirt and undershirts and give us a hot and later a cold shower to wind up with.

…..rifle drill with our Lee Enfields (when we just got them about two hundred of us took ours up to one of our companies, in exchange for their “Sam Hughes” , as we call the Ross, they were holding a front at that time.

Why the Canadians ditched the Ross Rifle in WWI.

Pay day I felt rich besides being sick of cheese and bread and vice versa so on my three dollars set out for some eggs, etc. I had three fried, two bread, two milk and some chocolate bars (only kind). All afternoon and night I was sick as a dog but had to keep working.

We are the last Coy. to have a front of our own – it lasts days this trip. The trenches are good, dry and clean as a whistle. Our worst enemy is rain and it’s time for some as it’s quite four days since the last storm.

11th – In trenches as reserves one full day. Having a fine time, no danger here. Lots of rats, though. Good eats – while up here we cook our own.

Colourized personal photos of British soldiers relaxing before the Somme. These photos give you an idea of life away from the trenches but still close to the Front.

In his next letter George describes his living conditions. It seems his Mama hasn’t quite taken on board what fighting in France really means.

France Sept. 16, 1916 , 100-150 yards from the enemy

While in reserve trenches there were four of us per dug-out. The dug-out is just a little higher than your head when you sit down. About six feet square and partly built into the ground, partly sand bags with a sheet iron and sand bag top. Ours had a half wooden floor.

WWI dugout recreated at the Hampton Court Palace Flower Show

Probably not quite like the recreation of a dug-out I photographed in 2014.

We put a fireplace into it and had our meals served table d’hôte, sometimes perfection, sometimes otherwise. […] At one dinner or better to distinguish it, call it a banquet – we had buttered toast, cocoa, two kinds of jam (saved from former meals) fruit cakes, sardines and oatcakes, gingerbread, pork and beans (for two), fried ham (or whatever it might be) and cold beef (not bully). Isn’t that some class, no wonder I was sick that night.

The dug-outs are all the same and we stretch out as often as the chance comes along. […..] The trenches are necessarily narrow and the “fire-step” takes all available space so when someone comes along it’s a case of down with your feet from the opposite wall to let the person pass. I had a great laugh when I read your letter re: “beds” – no we don’t get into anything like that. I can sleep sitting down or standing up if there isn’t any place else. Today I made a periscope of my mirror and a stick put up on the palisades. It is only necessary to glance up to see if Fritz is making any move.

Eating at the Somme. August 1917. photo: LAC—PA001596

Front Sep. 23, 1916

You will be interested to know how we get food – water, carried in a tin formerly used for oil or gasoline, holding two gallons. The shape is square cornered, so as to take less room for waste space in the wagon. Bread, comes in bags, six four pound loaves; butter (if any) in tins one pound each, pork and beans, bully beef, three-quarter lbs. jam in tins; all packed in a bag. Bacon and ham half cooked so as to heat it if we get a chance. Tea and sugar comes for the platoon (57) to be made if the cook’s kitchen is not in reach. When they are around we get a hot mulligan for dinner (made of Maconochie’s rations and anything else available.) Mac’s is a mixture of beef, beans & potatoes and goes good especially so a couple of days ago when we had a real good dinner of it.

Maconochie’s Rations

For four days we were at a support trench – the dugouts were of the kind I told you. We had no fire-place and as it was quite cold and rains often I set to work and got the other three worked up to building a fire-place in it.

We had a good deal of experience while at that front – too much for me – we had an old trench buried under the one in use and the thing wasn’t especially enjoyable.

Several of our boys were on working parties to “no man’s land” returning with turnips – they said there were all kinds of them also potatoes growing out there.

The dug-outs were crowded with rats but I haven’t any strangers [lice] yet. The rats went into my haversack and ate all my biscuits which made up part of my emergency rations….

Today we had a relief and I got one of the jobs as a guide when on the way back I “spared” a half ripe pear – wouldn’t I like to get into our old Pictou orchard for a half hour.

In October, 1916 George started training as a machine gunner.

France Oct. 1916

Some of the troops have had to make a bottle of water last three or four days and then go without for a while…

At present there are three of us from the 78th taking a machine gun course at a French town near the coast. We are having a ‘jake’ time and will get a week of comparative rest…..I seem to be in pretty fair luck so far as to courses. This is my third now and next I report to get into our M.G. section so as to be able to be of some use. The M.G. is practically the only gun or rifle of any use in this section of the country. We have now seen the shell ploughed fields and they are all the papers say.

Road on the Somme, October 1916.

LAC 3194754

Am going up the line right away as before I haven’t yet connected with the M.G. Coy. Rec’d a card from Cyril – he is OK. Don’t worry about either of us as we are both jake and I may not get an opportunity of writing for a couple of weeks – mail service will be very poor from the line I expect.

France Nov. 24, 1916 (This was the only letter addressed to his “Dear Papa”.) George had received a letter of Oct 22 and a couple of days later was off to the trenches – no time for even a field card. Now he’s back from the Front.

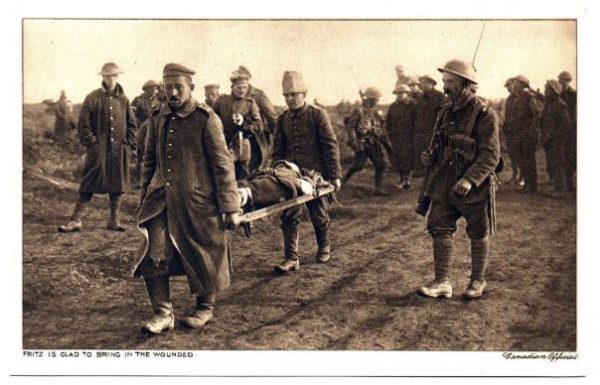

A number of prisoners were taken – everyone treats them to cigarettes and they carry out our wounded, also any of their own who happen to be in our lines. The usual trouble of going beyond the objective happened – the boys went over and of course, even our artillery caught a few of them.

From a series of postcards published by the Canadian Daily Mirror. Photograph by Ivor Castle, who took hundred of photographs at the Somme between mid August and November, 1916

It is awfully cold or was so while we were up last time – snow, ground frozen, sleet and then on top of that rain, and then the worst enemy we have – mud. Well, I must get ‘dressed’ ready to go for new equipment (Webb) as our Canadian outfit has all been changed except the harness. We are quite “Imperial” now and our reinforcements won’t recognize the old Canadian 78th.

Canadians return from trenches on the Somme Nov. 1916

LAC 3194728

From now on I will be with the Lewis Gun squad as the Companies get the guns and the former M.G. Co. goes into reserve. There is no danger attached to the job.… this last trip the two boys who were up with me at Etaples, also myself, were given the job of explaining and getting ready about a dozen boys to come with us on the guns.

One of our boys who went over was looked after by a Fritz who stole food for him, disguising himself in one of our great coats and speaking perfect English, after three days he got a chance to bring him in and everyone made quite a fuss over him – he had a slight leg wound himself and two soldiers took him to the dressing station – they didn’t even have rifles with them.

The casualty lists will be quite startling when you look over them and see a number of 78th or numbers beginning 48—. We get the papers here from the Peg…

The total of Canadians killed, wounded and missing on the Somme was 24,000.

George continues writing letters in moments snatched between training, duties, maintaining the dugout and coping with cold weather. Here he touches on one of the most important armaments to be tested in the Great War.

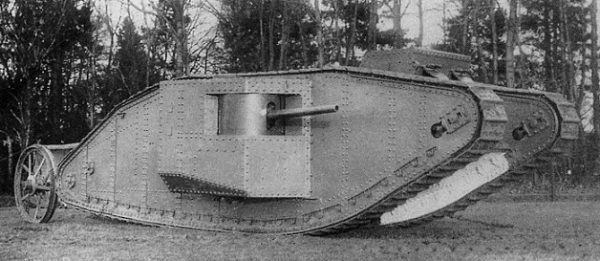

British Mark 1 Tank

France Dec. 13, 1916

The first thing that strikes me is the “tank” – you have very likely seen a good picture in the “free Press” as a copy reached here over a month ago with a good one in it. There is nothing so wonderful to it from what we have seen of them (never yet in action) but the boys who have been in action with them place a great deal of confidence in them – there are two kinds of machine gun and “small shelters” with M.G. – they are quite large and travel slowly but as for invulnerability, why I have seen a couple “put out of business”.

Again he tries to reassure his family he is safe where he is.

At this front the Colonel told us in a joking way that the women could come up to the trenches and sell us chocolates and biscuits.

In December’s letter George responds to his family’s alarm over news reports, and his mother working to raise funds for the soldiers.

France Dec. 14, 1916

Your letter Nov. 12: The report you received was absolutely unreliable. On Oct. 13 we had our first working party at our last post and of course it was at night – there were nine killed and twenty-seven wounded instead of twenty-three killed and an officer. There was one slightly wounded – he was hit in the shoulder by a small piece of shrapnel. The reason for all the casualties was not because it was our unlucky day. You are working too hard trying to raise funds for different things…

Yours Nov. 14: The M. Gunner is not one bit worse off than the man in the platoon –a gunner doesn’t go out on working parties and seldom has any worse than an outpost duty.

(during his latest trip to the trenches)… during my guard a couple of Fritzies came across maybe to examine our barbed wire. I wounded one and got him prisoner and the other was helped back to his own lines…. I am satisfied we won’t be in the War for a few more months.

Don’t worry about me because I have a jake job.

Typical trench

Apologizing for not writing regularly in the past two months:

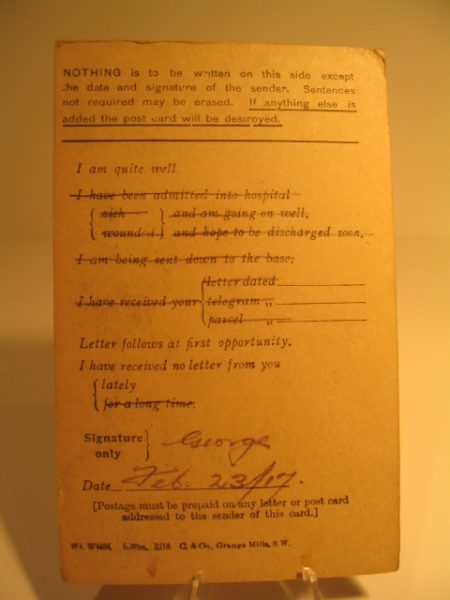

France Jan. 9, 1917

..a whiz-bang (field-card) doesn’t quite say enough.

A whiz-bang or field card was a simple postcard which let a soldier tick off what his current situation was. He was not allowed to add any message to it, or it would be destroyed.

Whiz Bang

.. all of us agree that we have travelled quite enough through France.

D.S.O. Distinguished Service Order

Today, our Colonel, the Col of the 38th Bn and seven or eight of the men were decorated with D.S.O.’s and D.C.M.’s also a military medal.

Canadian Lance-Corporal receiving the D.C.M.

Distinguished Conduct Medal

We go into the line again in a few days

I wrote to Mrs. Turner around Xmas to thank her for a swell scarf and cigarettes she sent me. This last time up the line I had to leave the scarf – It was a Jaeger and very fine and the “other things” [lice] got into it so I had to take it off.

A heavy howitzer on the Somme, Dec. 1916

LAC 3194242

Jan. 29, 1917

The telegram [Telegraph?] published an interview of a Col who had seen the 78th and in the interview they said we had come out of the Somme with 350. You can take it for what it is worth. In every case there are very large numbers of sick – bad feet, etc.

Xmas: Well you didn’t have a very gay one did you? It is too bad but no one seems to be handing out the tickets for Canada yet so I have to stay for awhile yet.

The Royal Bank sent their ex-employees a hamper from Harrod’s at Christmas.

The hamper ordered from Harrod’s as a gesture to RBC employees serving on the Front. Xmas 1916

I wish you would ask Bird to thank the members of the staff that I know – as there is a great big parcel on the way from London.

At times when a field card comes will you make it do for a letter as it is bitterly cold and has been for the past two or three weeks.

George’s next trip to the line was interrupted by two bouts of bronchitis, back-to-back. According to documents he was sick from Feb. 11-21, 1917. While he was at the dressing station his comrades raided his haversack.

France Feb. 12, 1917

We have had a fairly uneventful trip in the line, and a couple of nights ago I got a touch of bronchitis and the M.O. is sending me to the hospital for a little rest and a change…. You remember how I used to get a couple of weeks of it about Feb. or March every year. I am sending Gladys a field card with “bronchitis” spelled on it – I wonder if she will get it or if it is destroyed?

Will you thank Mr. Ingram for me – really his box was immense and such a packet of eats. Everything was swell and it hung out for four or five days so you can imagine the quantity when there is always a hungry half dozen sticking around. Incidentally the same bunch stripped my haversack when I went to the dressing station and although there is nothing of any value yet it is funny… one of my chums was there and he got my knife, fork etc that the bank sent, also a towel.

Mar 8, 1917 France

Sometimes I wear the homemade sox out and often they are so full of mud that they have to be thrown away. While at the last town I had four pairs washed and if things aren’t too busy this Spring there won’t be any trouble in doing the same right along.

The U.S. is quite a joke to everybody now.

Expect to spend my birthday in the line and the box will be fine, should it just come that day, it will be more so, but one day is just the same as the next. … Thanks for the good wishes. I expect the next time to receive them in person instead of by mail.

Thanks very much again for the fine parcel en route – if you should ever send anything of value again like the watch from Papa, please register the parcel or send whatever it is separate – registered.

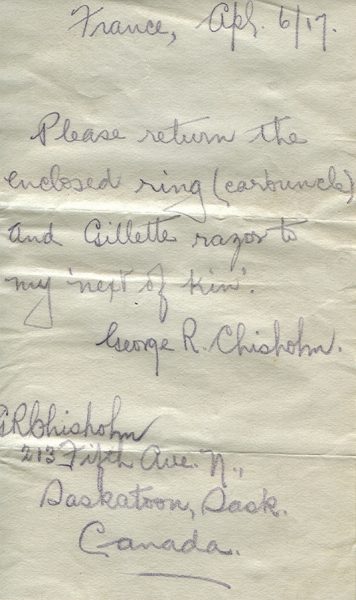

On Good Friday, April 6th, 1917, George writes a note and encloses his ring and razor with it. Perhaps he gave it to a fellow soldier behind the lines for safekeeping. His parcel from Papa had arrived safely and included a black faced watch for his birthday, Mar. 15th.

A note he wrote three days before Vimy.

from: Canadian Letters and Image Project

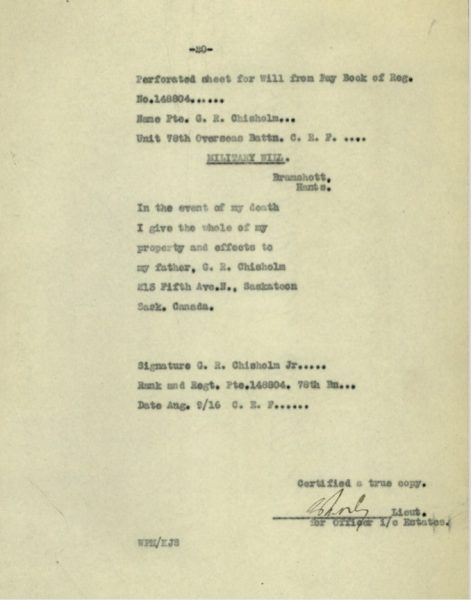

This is in addition to the short will form that every soldier fills out.

George’s will signed Aug. 2nd, 1916

LAC RG 150, Box 1685 – 28

Despite the fact that George enlisted in the Winnipeg Grenadiers, an infantry company, he complained that at first he was doing night duty repairing trenches. He then gets trained on the Lewis gun and has some time acting like a real soldier, but not enough for him. Excerpt from letter dated Jan. 29th, 1917:

…..we are supposed to be fighting as you think but instead about half and more of the time we are put in doing working parties – carrying lumber for dug-outs, trenches, etc. – sand bags from the mines etc. and for all the ammunition I have used since coming from Belgium I could put it in one of my pants pockets.

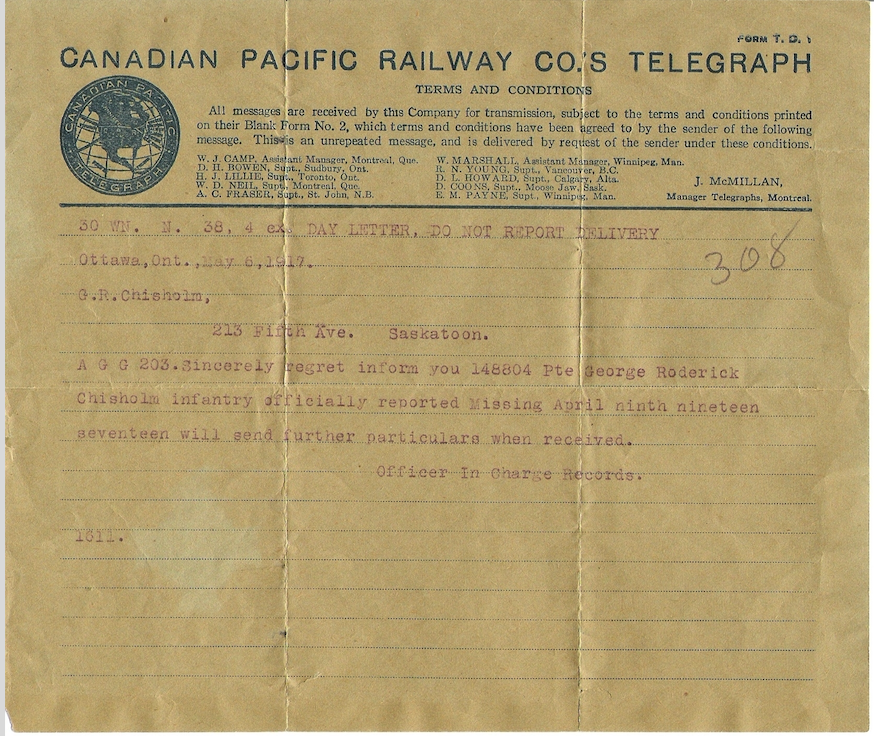

At 5:30 on the morning of Easter Monday, April 9th, he gets his wish and goes over the top at Vimy Ridge. Nearly a month later, his father receives this telegram:

May 6th, 1917 telegram reports George is missing since April 9th

“30 WN. N. 38 4 ex Day Letter, Do not report delivery

Ottawa, Ont,. May 6, 1917

G.R. Chisholm

213 Fifth Ave. Saskatoon

A G G 203. Sincerely regret inform you 148804 Pte George Roderick Chisholm infantry officially reported Missing April ninth nineteen seventeen will send further particulars when received.

Officer In Charge Records.

1611″

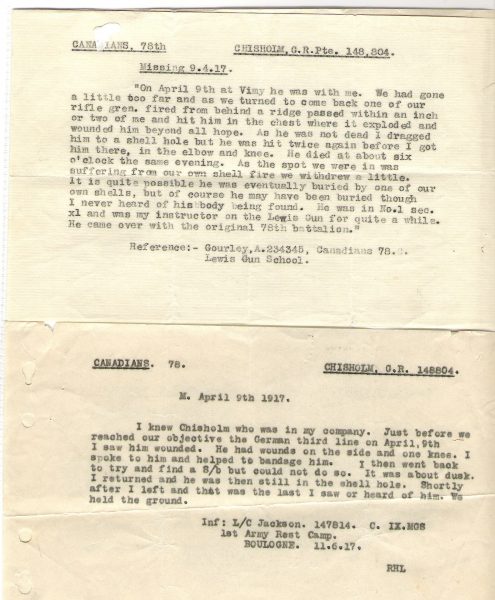

His father, also named George Roderick Chisholm, appeals to everyone he can think of. There are numerous letters to the Red Cross, appeals to the Overseas Military Forces of Canada and Lieut. Col. Robertson. On June 21st, 1917 he receives a letter from Mr. R. Whitley of The Royal Bank of Canada, Princes St., London. Enclosed were two reports from the Canadian Red Cross Society .

Mr. Whitley states:

“I enclose two reports sent to me by the Canadian Red Cross Society, from which you will see that two other men have stated (1) that they saw him killed on Vimy Ridge and (2) that they saw him wounded and that about dusk the same day he was still in a shell hole.

This last report by itself would leave us with some hope, but in view of the fact that we held the ground on which the shell hole was, I fear there is little hope that he can still be alive.”

Two accounts of George’s death.

“On April 9th at Vimy he was with me. We had gone a little too far and as we turned to come back one of our rifle gren. fired from behind a ridge passed within an inch or two of me and hit him in the chest where it exploded and wounded him beyond all hope. As he was not dead I dragged him to a shell hole but he was hit twice again before I got him there, in the elbow and the knee. He died at about six o’clock the same evening.. As the spot we were in was suffering from our own shell fire we withdrew a little. It is quite possible he was eventually buried by one of our own shells, but of course he may have been buried though I never heard of his body being found. He was in No. 1 sec. xl and was my instructor on the Lewis Gun for quite a while. We came over with the original 78th battalion.” Pte. Gourlay 234345 [spelled incorrectly “Gourley” on the note]

“I knew Chisholm who was in my company. Just before we reached our objective the German third line on April 9th I saw him wounded. He had wounds on the side and one knee. I spoke to him and helped to bandage him. I then went back to try and find a s/b [stretcher bearer] but could not do so. It was about dusk. I returned and he was then still in the shell hole. Shortly after I left and that was the last I saw or heard of him. We held the ground.” Lance-Corporal Jackson 147814

George’s family do not give up hope, and continue to appeal to everyone they know.

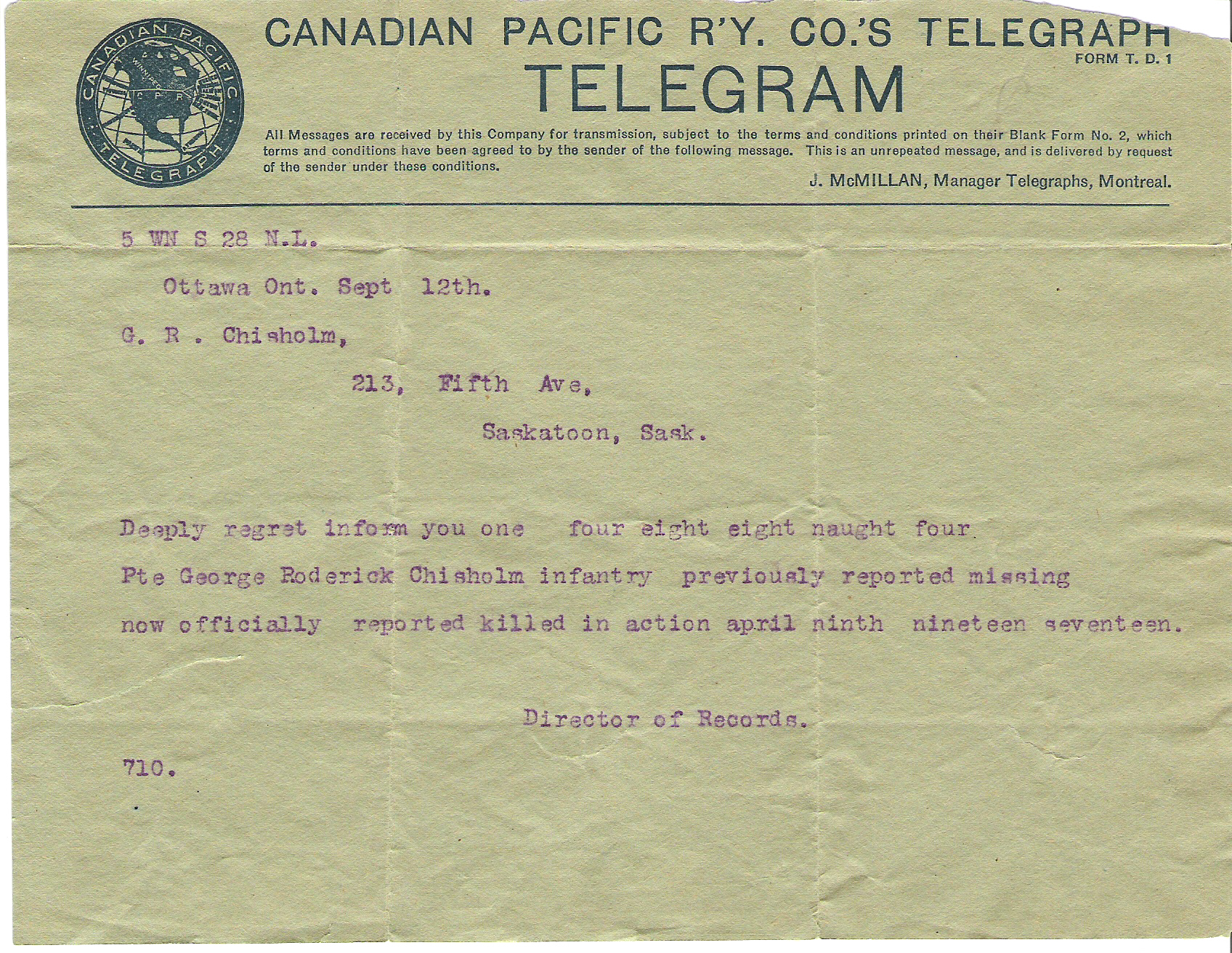

Finally, on Sep. 12, 1917 they receive this telegram.

CP Telegram officially reporting G.R. Chisholm’s death five months after Vimy.

They must finally accept the loss of their youngest son, the handsome, musical George who was going into banking like his father. He is honoured on the RBC (Royal Bank of Canada) website, in a Roll of Honour. Their entry reads:

“George Roderick Chisholm, Jr.

PRIVATE CHISHOLM, born at Pictou, Nova Scotia, March 15, 1897. Home in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Joined Saskatoon branch, July 2, 1914. Enlisted from Saskatoon branch, in the 78th Battalion, April 15, 1916. Present on the Somme and Vimy Ridge. Killed in action at Vimy Ridge, April 9, 1917.”

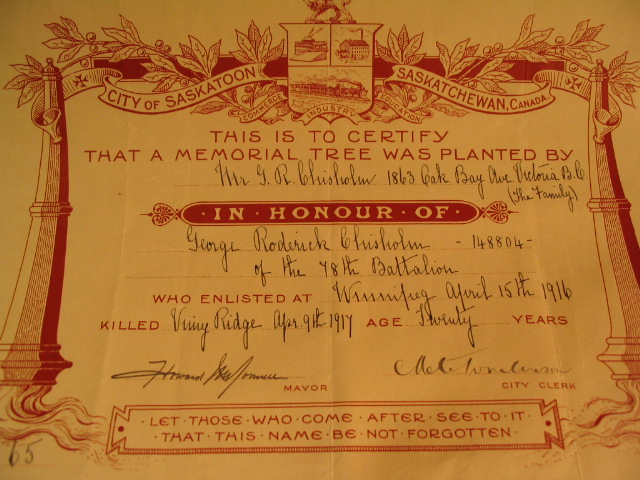

Another memorial was planted in Saskatoon.

Memorial Avenue of trees in Saskatoon, SK

At some point after the war the family moved to Victoria, BC, where their house still stands.

The Chisholm family home on Oak Bay Ave. Victoria, B.C. They moved after WWI.

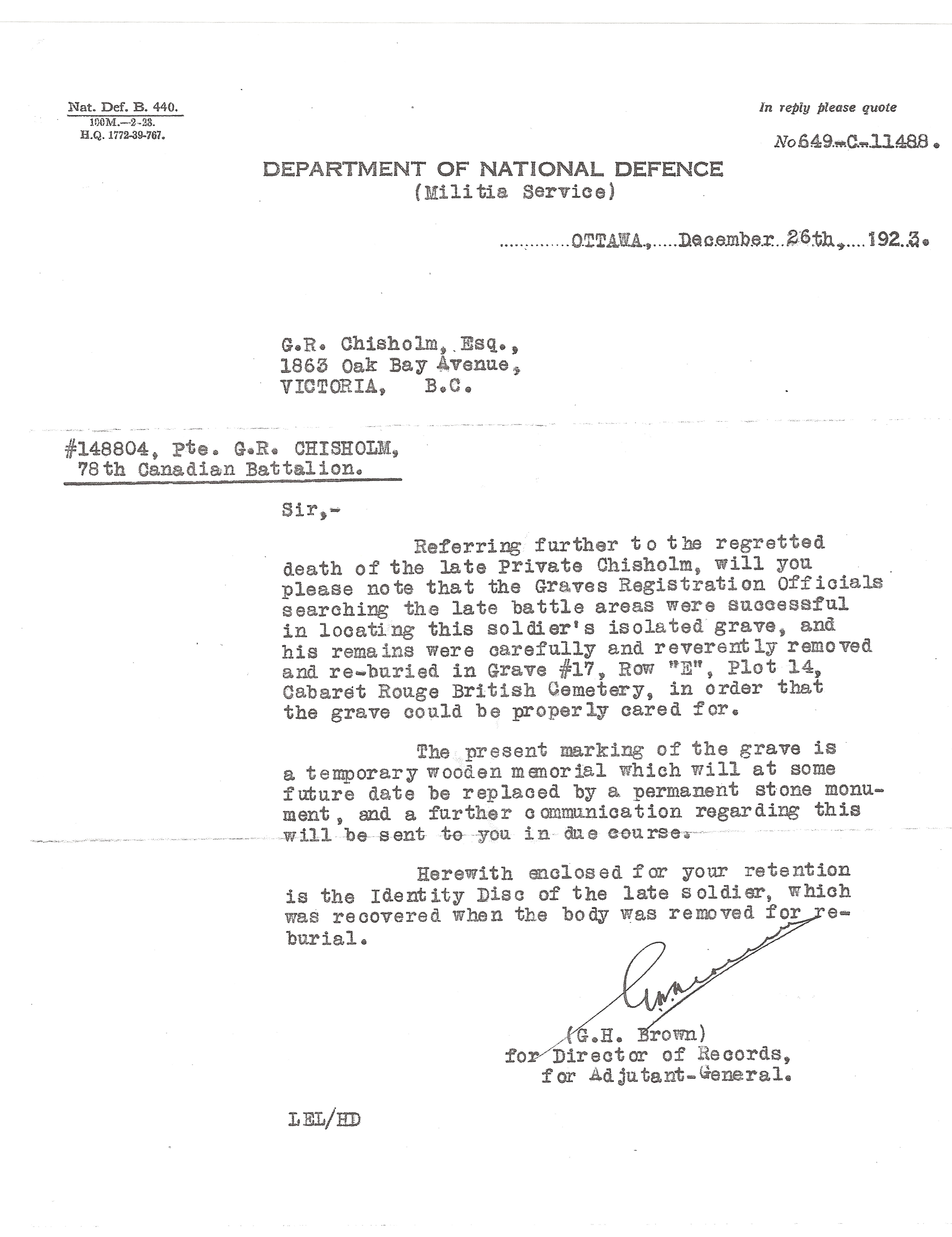

Then, in 1923, just when one would think some of their pain had receded, they received this letter and its enclosure:

Dec. 26, 1923

George Roderick Chisholm’s identity disc, dug up in 1923, still pitted with Vimy mud.

His remains lie today in the Cabaret Rouge Cemetery in France and are looked after by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

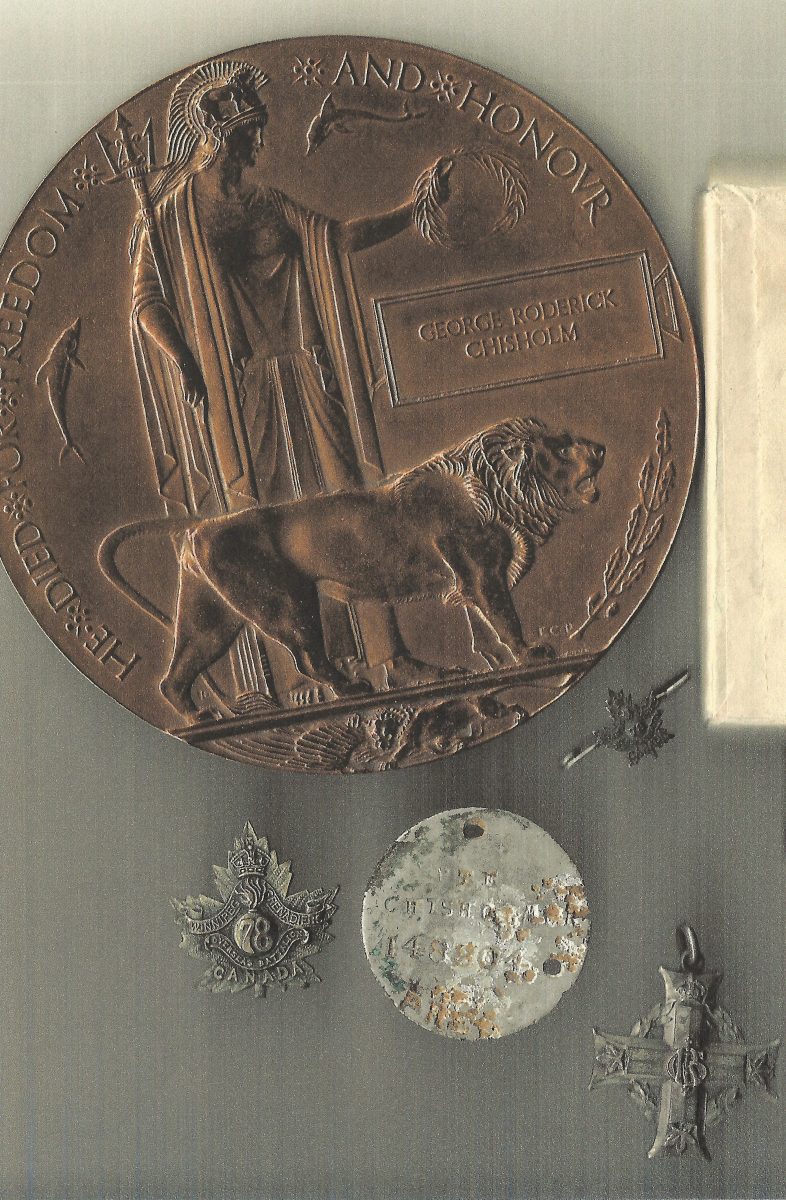

His mother received the Silver Memorial Cross with his name engraved on the back.

The Silver Memorial Cross awarded to wives or mothers of fallen soldiers

Reverse side of his mother’s silver Memorial Cross

The family also received his medals and the large Bronze Memorial Medal also known as the ‘Death Penny.”

The British War Medal and the Victory Medal. George’s name is inscribed on the edge

Death Penny, identity disc, memorial cross and two 78th Battalion pins given to his sisters

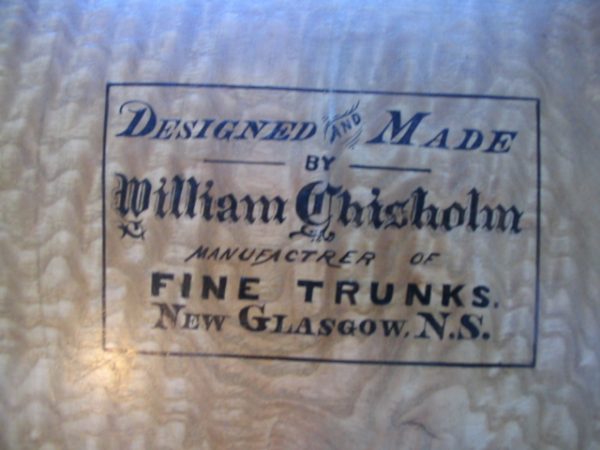

Who had kept all the medals, pins, letters and cards in this archive I was fortunate enough to study?

It had literally arrived in a treasure chest; a beautiful wooden trunk lined in pink silk. The trunk belonged to a spinster, Ida M. Chisholm (known as Bird in his letters) who kept her brother’s medals and documents all her life.

Chisholm Trunk

Trunk maker, another Chisholm

Secret compartment in the trunk where the letters and medals were hidden

I took everything home and started to read. It took a long time with some of the letters worn thin at the creases, the faded ink and tiny handwriting. I read everything, without stopping, until my eyes were red with strain and tears. At the end, I felt close to George and his WWI experiences culminating at the battle of Vimy Ridge, and I hope those of you who read this will feel the same way.

Here dead we lie, by A. E. Housman

Here dead we lie

Because we did not choose

To live and shame the land

From which we sprung.

Life, to be sure,

Is nothing much to lose,

But young men think it is,

And we were young.

Cabaret-Rouge Cemetery, Souchez France

Image by Wernervc