Have you ever stopped reading a book that everyone is raving about because you just found it…..boring? Have you persevered to the end of dull books just because you think you might learn something and afterwards regretted all that time you will never get back? I am here to tell you that sometimes it pays to read to the end of even the most yawn inducing volumes.

If you look at the top of this blog you will see a Book List page where I tell you why I set myself a goal in 2014 to read a lot about Burma and which books I read. Most of these would not have been books I’d normally choose to read for fun, but by the end of the year I was a convert to the non-fiction, history and WWII genres. I forced myself to read many books that previously I would have ditched after a few pages. As well as the books from my uncle’s library I started looking for more. So, a few weeks ago I spotted a book at a local secondhand bookstore, Russell Books, after I scrutinized all the shelves in their Southeast Asia section. It was written by a man outstanding in his field and literally, Out Standing In A (Burmese) Field. It was “The Golden Road to Modernity: Village Life in Contemporary Burma,” by Manning Nash, published in 1965.

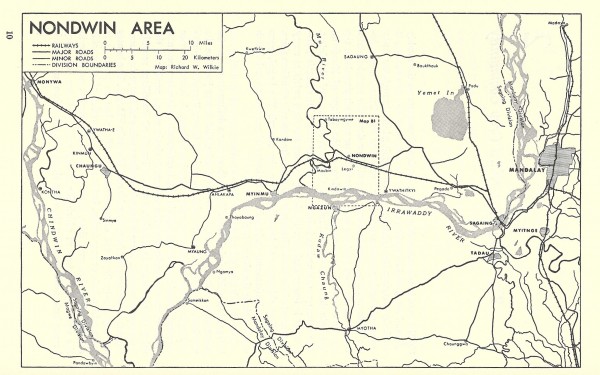

Dr. Nash was a member of The American Ethnological Society, The American Anthropological Association and The Royal Anthropological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. He taught anthropology at the university of California, the University of Washington and at the University of Chicago, where he received his PhD. He had done field work in Guatemala and Mexico, and later in Malaya. His field work for this book was done in 1960/61, just before the infamous military takeover that locked the country away until 2012. He chose two villages in Upper Burma near Mandalay: Nondwin, a mixed crop community and Yadaw, a rice growing community.

It could only be read in short doses while my mind was wide awake. It was no good reading it before bed, unless I wanted to fall asleep suddenly, like a parrot with a cloth over its cage. It had no photographs of the area or even drawings of the thatched huts or a bullock cart. It was as sere as a summer in the Dry Zone of Upper Burma. I started referring to it as The Most Boring Burma Book in the World.

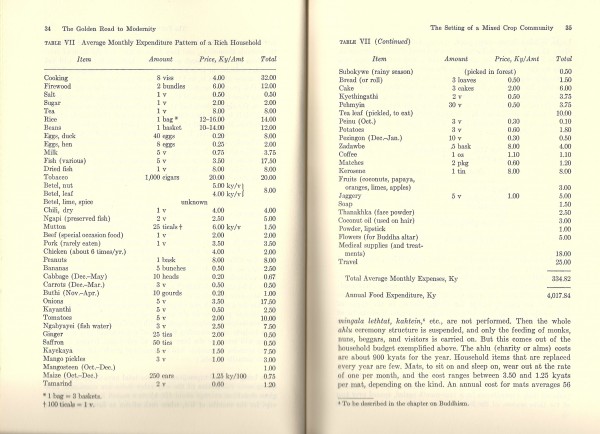

After reading a good introduction about the basic history of Burma I faltered at the first hurdles of maps and tables. Ask anyone who knows me and they’ll tell you: maps and this woman do not get on. I have been known to search for a friend’s house on an entirely different street one block parallel to hers and nearly convince myself her house had shape-shifted since I was last there. Nash’s maps were black and white line drawings that I itched to colour in. Shouldn’t the Irrawaddy be blue, the fields green and the scrubland beige? And then there were tables: Crops worked with acre and cultivator totals, return per acre of cotton or sesamum (sesame seed), a graph of landholding sizes, so many tables quantifying minutiae …..but then I came to Table VII: Average Monthly Expenditure Pattern of a Rich Household. I was hooked.

This table and its companion for the Moderate and Poor families made the village of Nondwin spring to life. I read on and was rewarded with a description of life in the Burmese countryside that with few changes could easily be written of the villages today. The farmers In 2015 might have cellphones but they still use bullock carts and wooden ploughs. I’ve seen satellite dishes on houses at Inle Lake but the cultivation of floating gardens continues. Cooking over open fires, the wearing of the longyi and the morning ritual of feeding the monks is normal, and Buddhism is still the main religion.

Woman making rice crackers over a charcoal fire. She makes up to 400 per day and sells them in the market.

I had a companion as I read. The previous owner of the book, David S. Moyer according to the bookplate, had pencilled parentheses in the text and N.B’s in the margins. Normally this marking of books annoys me no end and I find the more emphatic the underlinings the less likely the reader has finished the book but Mr. Moyer obviously read every word and fully grasped what was important. I like to think, but have no proof, that he was a graduate student attending one of Nash’s classes when he pencilled the notes in this book.

The reward for reading on was finding nuggets of gold like this selection of his nota benes:

“The villagers have the material equipment of a mode of life developed centuries ago and a mental outlook more closely geared to that than the modern world, but, at the same time, they are acting members of a working Asian democracy, and they are participants in the political and economic processes of transformation.”

“Toward what is seen as government, villagers take a stance akin to what they take when dealing with nats (the animistic beings peopling a good part of the village conceptual world): They try to ward off or to minimize this potential evil.”

“Women are full, functional members of society, whether they marry or not, as are men, and of course the unmarried are built-in parts of the social structure, not anomalies. The great overlap in the sexual division of labor makes it simple, on the side of the ordinary business of keeping fed, groomed, kempt, and housed, for single persons to live alone. Men can sew, cook, baby-tend, wash clothes, and shop for food. Women can work in the field, drive bullock carts, chop wood, and be prominent in market transactions.”

My favourite is :”Government is one of the five traditional enemies, along with fire, famine, flood, and plague.”

Since Burma has had little to do with Western countries for the past fifty plus years, it has been frozen in time and many of Professor Nash’s meticulous observations still hold true in the country today, whether it’s rural vs urban populations, the educated classes vs agricultural workers, or the common people vs the ruling elite in Naypyidaw. Considering there is going to be a free (ish) and democratic (sort of) election in Burma at the end of 2015, I think anyone in the Western press surmising about the outcome would do well to study “The Golden Road to Modernity” before coming to any conclusions. We know what happened recently in the UK elections and how the polls and pundits got it so wrong. To find gold you have to sift through masses of heavier material; I hope the election predictors for Myanmar do their homework and get it right, even if it means reading The Most Boring Burma Book in the World.

I wandered across “In Praise of Boring Books” while Googling Yadaw or Nondwin, Burma. I remember those place names from a class I took at the University of Chicago in 1967. Imagine my surprise to find a picture of the textbook, or at least a picture as I remember it. It wasn’t all that boring in the hands of my teacher Manning Nash. I would be happy to share my story about this book with you, and to share what I may know about David Moyer. Just let me know that you’re out there.